The Political Meaning of Monitoring in Restricted Civic Space

Citizen monitoring as a way to enhance public accountability has become popular globally over the years. In the Philippines, where several successful citizen monitoring initiatives have been noted, practical experience has shown how political context is a key factor that shapes the conduct of citizen monitoring and what it can achieve. When a political context becomes unfavorable, what does it mean for the practice and characteristics of citizen monitoring? What does this tell us about what networks of citizen monitors need to continue taking strategic approaches to accountability at the frontlines?

G-Watch: doing monitoring differently

A conventional notion of monitoring views it as a technical process. It is about gathering data and information about the implementation or operation of a policy, project, or service to analyze or assess performance. It can be internal to an implementing agency, or carried out by independent third parties.

G-Watch is a citizen accountability movement in the Philippines that monitors public services, as part of its broader aim to deepen democracy. Founded in 2000 as a university program, it spun off 17 years later to become a citizen movement that undertakes monitoring, action and research on transparency, participation, and accountability across the country.

G-Watch monitoring, especially in its early years, has included all elements of the conventional notion. G-Watchers check compliance to standards of service delivery in health, education, social protection, and other sectors through actual observation and feedback to diverse stakeholders. By standards, G-Watch refers to what duty-bearers need to comply with – be they laws, guidelines, plans or targets.

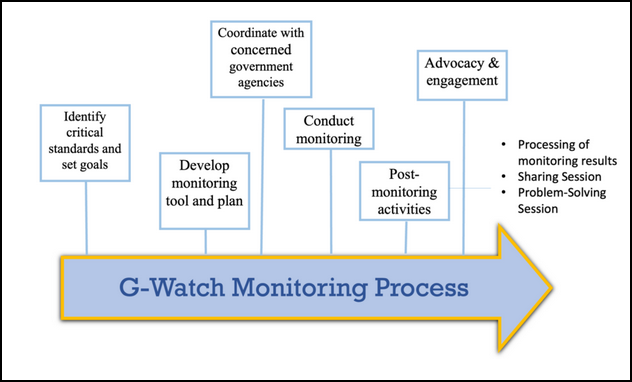

Observable monitoring points derived from the standards form the basis of a monitoring tool used to gather information, during which G-Watch coordinates with government offices and officials. After analysis, the monitoring teams derive recommendations to government, and conduct advocacy and engagement to push for their implementation (see figure).

Central to G-Watch accountability initiatives are the tools that monitors use to check compliance to standards. G-Watch monitoring tools are usually ‘yes or no’ questions on whether standards are complied with, and/or survey questionnaires to stakeholders on their experience in availing of or participating in a policy or service.

Beyond the conventional notion, and in contrast to third-party monitoring by outsiders, G-Watch monitoring deliberately involves strategic local stakeholders, including communities and citizens who are beneficiaries of projects or service users. It also does not just stop at findings and performance analysis, but puts forward and advocates for solutions.

There have always been substantial technical and transparency challenges at the boundary of state and society raised by public service monitoring. As an action research organization focusing on scaling accountability and citizen empowerment, over time G-Watch’s monitoring has become far more than just a technical process. As the organization has rebooted to become a citizen movement for accountability, and civic space has contracted, a multitude of new challenges and risks have added new layers of political meaning to monitoring, and led to a far greater emphasis on citizen organizing at the heart of G-Watch monitoring.

In an unfavorable political context, citizen monitors face adversity and resistance, a seemingly impossible job every step of the way. Fortunately, in the case of G-Watch’s recent work organizing around the right to health, overcoming challenges and hurdles has also served to galvanize and empower.

The everyday challenges of monitoring

In the Philippines, questioning those who are considered at the top of society (in terms of age, socio-economic stature, or political position) is unwelcome or frowned upon. This conservative aspect of culture is a prevailing undercurrent that discourages accountability efforts.

One can say, then, that legal guarantees which enable citizen action for accountability try to overrule or transform this existing cultural norm. When the government says it is supporting and enabling participation, it serves as leverage for reformers and advocates to assert and enable legal provisions, despite the prevailing cultural constraints.

G-Watch tries to address the cultural challenges by framing accountability as co-construction between citizens and government. This framing turns the contestation automatically entailed in challenging cultural norms into something positive and collaborative that can create progress towards common ends. Achieving this, without compromising civil society independence, is a complex formulation that is best supported by a favorable politico-legal environment.

There are usually three main challenges that citizens confront in dealing with the government in monitoring: uncooperative government officials; processes that remain inaccessible given gaps in the laws; and inaccessible, inaccurate, incomplete, or useless information.

Access to public information and to the processes and officials involved in a given policy and service is crucial for G-Watch to undertake monitoring; some public information is needed at every stage of engagement with government. To illustrate, if G-Watch is unable to get information on when a process of bidding for government contracts will happen, an observer cannot attend, and G-Watch will not be able to monitor the bidding. Or if a G-Watch monitor can access schools, but principals will not provide plans or performance reports, assessing the performance of the school’s implementation of its learning continuity plan will be constrained. Or if a G-Watch monitor can access reports from the Department of Health or community-level health units, but the information is incomplete, inaccurate or useless, the analysis of the health unit’s performance will face many gaps.

In a favorable political-legal environment, access to public information, processes and officials are not that problematic. The likelihood of government officials complying is high, citizens have several points of leverage for making information public, including policy documents and mandate from the political leadership. This has been largely the case in some sites where G-Watch has had decade-long engagement, and where local core groups include many stakeholders, including from government. But even then, accessing accurate and useful information can be a struggle due to weak right-to-information culture in Philippine governance. Some information that is essential for monitoring – such as budget allocations per locality – needs to come from national government; if it is not available, accountability work on the ground is constrained even if the local context is favorable.

The experiences of volunteer-monitors from the Samahan ng Nagkakaisang Pamilyang Pantawid (SNPP) under G-Watch’s PRO-Health initiative illustrate the dynamics and range of these practical challenges of monitoring. SNPP is a national association of beneficiaries of the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program, a national conditional cash transfer program; its beneficiaries are among the poorest of the poor.

PRO-Health is an initiative that takes a strategic approach to public health service delivery by learning with, from and for accountability frontliners. It monitors three programs: reproductive health, First 1000 Days and mental health services. Twelve SNPP leaders are among the 292 PRO-Health volunteer-monitors, who have been recruited and trained by G-Watch to do monitoring in 13 sites across the country.

SNPP volunteer-monitors intnerview health serivce users

SNPP volunteer-monitors intnerview health serivce users

In visiting the health units, volunteer-monitors from SNPP encountered challenges including getting health workers to agree to interviews, and getting midwives to allow them to observe health units. Novi, an SNPP leader volunteering for PRO-Health in Cebu, recalled the excruciating experience of having to go back many times to local government offices and health units to request documents and set up interviews; other SNPP leaders in Samar, Mandaue and Lapu-lapu shared the same experiences.

In other areas, local governments were relatively receptive. In Alang-alang, Catbalogan and Tacloban, letters sent to local government officials led to volunteer-monitors getting endorsed to visit health units—but not without resending letters, and several follow-ups.

In Paranas, SNPP leader Wermay and her team also were able to meet the mayor himself after they sent the PRO-Health letter introducing the initiative and requesting a meeting. The mayor found the initiative promising and expressed support for it. However, even with this support, they also confronted challenges in monitoring the health units.

Based on the past experience of G-Watch, the challenge is to find strategies and tactics that will encourage, push, or even force government officials to act favorably on the monitoring results and pursue the needed reforms.

Having government allies, showing broad- based clout; using evidence effectively and demonstrating expertise; providing technical assistance; communicating and coordinating effectively with government; and sharing best practices or encouraging government officials to be model public servants, as possible subjects of “faming” are some of the approaches G-Watch has used to generate favorable responses from government in the past.

At the time of writing, PRO-Health monitoring is ongoing. It is expected that there will be challenges as duty-bearers are asked to respond to monitoring findings and recommendations. The above approaches to generate government action and response and what it will take to effectively engage government in a constricted civic space will be other key areas of reflection in the next phases of PRO-Health’s monitoring and advocacy work.

Growing risks as right to participation gets contested

The three main challenges discussed above have become almost a norm in many localities in the Philippines; shrinking civic space makes them worse. Now, not only are government officials uncooperative, but some turn hostile. Not only are processes inaccessible, but there are officials who actively stop access of citizen-monitors to official spaces. Not only is information inaccurate, incomplete and useless, but it takes a lot more effort to obtain any of it at all.

Given worsening conditions of civic space, citizen action for accountability entails greater and more serious risk. In a context where the government does not support or enable civil society participation and instead curtails it, the act of participation alone—especially to seek accountability—can be viewed as disruptive or radical. When the political leadership is repressive and denies even basic human rights, threatening freedom of expression, right to assembly and the rule of law, becoming involved in accountability efforts automatically poses security and safety risks to citizens who now are not just working to improve services and policies, but are also fighting for their most basic rights. This drastically increases risks and threats to what, in favorable politico-legal contexts, could have been constructive citizen action.

These growing risks require more and different sets of capacity from citizen monitors and the civil society groups that support them. Even in favorable contexts, there are already challenges to building the needed civil society capacity: when there are more demands from constituencies and partners, or more openings, citizen organizations must have greater capacity to respond to the demands and occupy the new spaces that have opened. On the other hand, if there are more challenges, citizen organizations must have greater and different capacity to overcome them. Do civil society groups have enough numbers, technical know-how, and resources to conduct monitoring and overcome the growing and unending challenges in doing it? How can the capacity of civil society to monitor be built in such difficult contexts?

Overcoming challenges and risks as empowerment

With efforts to overcome the risks and challenges posed by constraining civic space, enabling citizens to do monitoring and come up with solutions becomes a painstaking process of empowerment. It demands more, takes a longer time and greater resources, and involves seemingly unending steps, including adjustments to keep the most fundamental rights and democratic processes and practices alive with citizens at front and center.

In PRO-Health, the conduct of monitoring in restricted civic space has turned into an organizing and coalition-building process. In a less favorable political context, the recruitment and training of monitors and the practice of monitoring can be seen as civic learning. The broadening of monitoring networks has become key to building collective countervailing power. Monitoring exercises are driven by a know-your-rights and claim-your-rights approach, and by a collective intent to improve governance. This is very different from the conventional focus of third party monitoring on data gathering as an end in itself.

G-Watch monitoring in a closing civic space has taken on the characteristics of a political struggle:

- Recruiting and organizing monitors is not just a simple process of sharing information. It now entails convincing citizens and groups not to be afraid, reminding them of their rights, and inspiring them by examples.

- Capacity-building does not only involve building the technical know-how of citizen monitors. It also entails equipping them with the knowledge of the basic concepts, legal foundations, and philosophical premises of advancing transparency, participation, and accountability. It includes developing the ability to meet challenges by adapting and responding.

- Monitoring now involves taking into account safety and well-being concerns, such as providing guidance for handling hostile government officials. Safety and security are included in briefing orientations for citizen monitors.

SNPP leader Wermay said that monitoring is empowering and a way to assert how government services should be provided. In a learning exchange, when SNPP leaders were asked if they can continue monitoring despite the challenges, no SNPP leader hesitated. “Kakayanin!” [we can do it], they responded. “Basta sama-sama sa PRO-Health [As long as we are together in PRO-Health].”

PRO-Health monitoring has served as a platform for the SNPP leaders and the rest of the volunteer-monitors, who are persisting against all odds to make a difference

PRO-Health citizen monitors at a G-Watch Briefing-Orientation Seminar on Health Budget Monitoring, February 2024

All images: G-Watch