Community Monitoring: Bringing People Closer to Public Health Services in India

In 2006, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of the Government of India took the bold step of making ‘community monitoring’—the idea that communities can provide feedback on the health system—an integral part of its ambitious public health initiative, the National Rural Health Mission. In India, where the domain of health is often perceived as being very technical, and communities as passive—even reluctant—recipients of services, this was nothing short of revolutionary.

But this revolutionary moment was part of a longer trajectory of change. This blog tells the story of how community monitoring emerged as a powerful tool to foster accountability in public health in India, and discusses how its meaning and practice have changed over the last seventeen years. It draws on the author’s experiences of participation in several community monitoring initiatives, and a recently released Accountability Working Paper, Activating Spaces, Scaling Up Voices, in which authors from implementing CSO SATHI trace the journey of community monitoring in the state of Maharashtra between 2007 and 2022.

India is predominantly rural, with a deeply ingrained caste system in which the bulk of the population belong to subordinate castes. The government is often referred to as mai-baap (father-mother, benefactor). In this context, integrating community monitoring as a formal practice within the health system required conducive conditions, and the acceptance and practice of several key concepts, including transparency, the right to know, advocacy, and social accountability.

The Emerging Practice of Social Accountability in Health

My first interaction with social accountability was in 1999, at a jan sunwai (public hearing) on how panchayat (local government) funds had been spent in Tehri Garhwal state. This initiative drew upon the experience of MKSS described in Suchi Pande’s Accountability Keywords blog, and was held in the region where the Chipko Andolan environmental movement—inspired by satyagraha, Gandhi’s idea of a unique form of ‘boycott’ through peaceful resistance—had originated in the 1970s. As social development activists, my colleagues and I were inspired by the idea of the jan sunwai. But as a community doctor, I felt that it would be difficult to translate it to the complex technical area of health, where community members often did not trust modern medicine for many of their health problems.

However, changes around the country—some of them connected to shifting international narratives and practices—gave cause for hope that ‘accountability’ in health might be possible. In the arena of family planning, for example, by the end of the 1990s, health activists and NGOs were becoming more comfortable in influencing public policy, and some senior bureaucrats in the health department were becoming more open to consultations and dialogues. This followed a decade of challenges to the Indian government’s heavy dependence on method-specific targets in family planning, which had led to the rampant practice of over-reporting of achievements on the one hand and forced sterilizations on the other. By 1994, the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo had included substantial participation of NGOs successfully calling upon governments around the world to accept free and informed choice in contraceptive use and the notion of reproductive rights. Inspired by these international events, several women’s health activists and NGOs in India had come together as Healthwatch, an advocacy network for reproductive rights. By 1996, the government adopted the Target Free Approach, which was followed by several progressive family planning policy initiatives.

By the time the year 2000 was drawing near, health activists across the world were keen to review progress around the World Health Organization’s commitment—made in 1978 at Alma Alta—to ‘Health for All by 2000’. In India, health activists across the country started organising regional health assemblies, assessing the status of health and healthcare. This process culminated in the Peoples’ Health Assembly in Dhaka in 2000, where Indian health activists organized themselves into the Jan Swasthya Abhiyan (People’s Health Campaign).

Drawing from the tradition of jan sunwais that had been started in Rajasthan by MKSS, health activists started organising jan sunwais on health and family planning, calling on health system users to share their testimonies. They persuaded the National Human Rights Commission to hold a series of regional public hearings around health in 2001–2002. These processes not only brought social and health activists together, but also gave them experience and confidence to talk to public officials and policy makers. Practices of accountability and advocacy that were emerging around the world found resonance in a robust domestic practice of social accountability in health in India.

Institutionalising Community Monitoring

Following the formation of a new Federal government in 2004, the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) was established in 2005. It was a response to calls for a change in the way the health system was organized. The NRHM emerged through a process of consultation in which several public health practitioners from CSOs associated with Jan Swasthya Abhiyan were invited to contribute. This was a unique experience in health-related policy formulation in India.

The overall aim of NRHM was to undertake ‘architectural correction’ of the Health System through increased funding allocation, and to strengthen rural healthcare through decentralization and increased community ownership. Quality and accountability in service delivery were considered a priority. The continued participation of civil society in the design, implementation and monitoring of the NHRM was ensured through CSO involvement in the Mission Steering Group and through the formation of two standing committees, including the Advisory Group on Community Action (AGCA) which included several members who had participated in social accountability initiatives through Healthwatch and Jan Swasthya Abhiyan.

The NRHM’s intention to achieve its goals by 2012 included several timebound operational and health outcomes and parameters that provided clear benchmarks that could be subsequently monitored. It was also relevant that while the NRHM was being designed, in 2005, the government enacted the Right to Information.

Community monitoring was included as a part of the three-pronged monitoring and accountability framework, along with external surveys and ‘stringent internal monitoring’. Help in designing the community monitoring component was requested from AGCA members, who were later also asked to pilot the design when it had been drawn up. State level AGCAs, in partnership with state-level CSOs, were established in nine states. Between 2007 and 2009, the pilot programme was successfully implemented in over 1600 villages in 35 districts. Following an evaluation, it was decided that community monitoring would continue under the stewardship and budget of the state-level NRHM authorities.

The Maharashtra Experience

The community monitoring pilot project was successful in demonstrating that empowered communities could provide feedback which led to strengthening of health system performance. It also increased communities’ trust in and use of public health. However, the process of sharing user experiences, many of which were an indictment of the performance of the health system, also made providers defensive. There were several debates in the AGCA whether the name ‘community monitoring’ should be changed to something that sounded less confrontational. In Maharashtra, the state AGCA opted to use ‘community-based monitoring and planning’, and at the national level ‘community action for health’ became the preferred terminology.

Activating Spaces, Scaling Up Voices offers a case study of Maharashtra that provides data and insights from a 15-year long practice of community monitoring anchored by the CSO SATHI. It raises pertinent questions about this state-supported effort to strengthen the accountability of public services.

SATHI adopted a multi-level strategy to amplify the voices of citizens and CSOs from the village to the state level. The process of community monitoring was facilitated through a partnership between the state government and several district-level NGOs and CSOs, coordinated by SATHI. At the heart of the strategy was the presentation of community-generated evidence followed by joint deliberation with public authorities for problem solving. This was achieved by appointing facilitators to work directly at the community level; as a first step they provided information about NRHM and the ‘entitlements’ it provided. Members of various health- related committees that had been formed to strengthen community ownership were briefed about their functions and the provisions of NRHM to facilitate transparency. This was followed by the preparation of village level report cards which were shared at jan sunwais at different level: health centre, block, and district. These jan sunwais brought together the functionaries of the public health system and citizens, face-to-face with data from the report cards.

Over the years the scope and spread of community-based monitoring planning increased, coming to include participatory budgeting as part of the decentralized health planning process, and more issues were included. The range of participating CSOs also broadened to include mass organizations, as well as development, health, and rights-based NGOs. This, together with strengthening of local committees and processes, enabled marginalized members of communities to participate in decision-making processes.

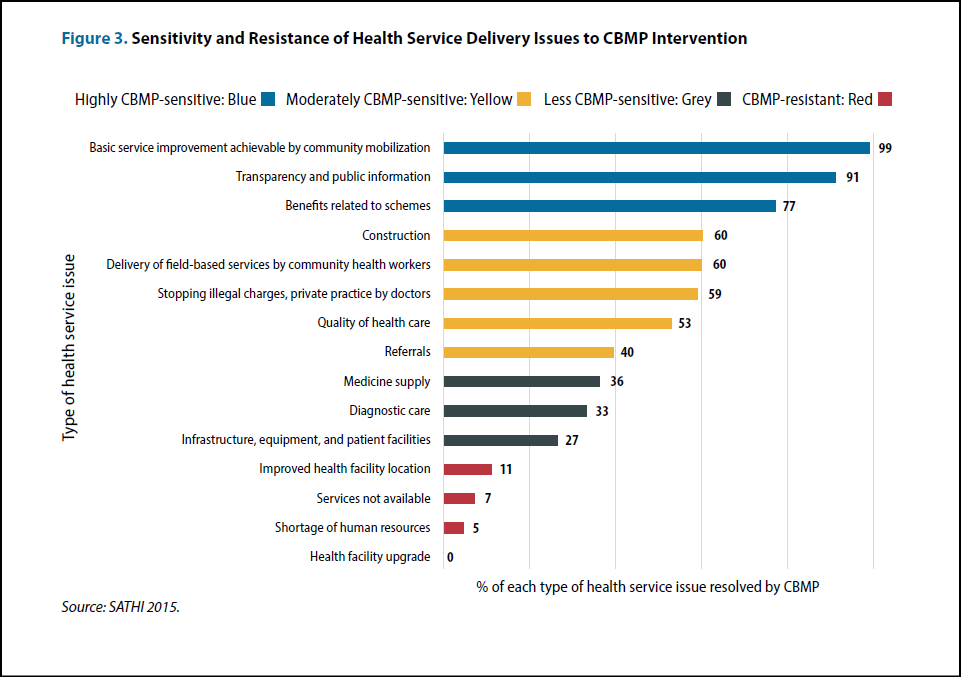

As shown in the figure below, community-based monitoring was successful in addressing locally resolvable problems, but not issues that required state-level interventions. Thus, problems like better delivery of services by functionaries, display of information about schemes, stopping unofficial charging, facility repair/constructions were resolved. However, staff shortages and facility upgrades could not be addressed through the CBMP process.

The fifteen-year journey was not without hurdles. The relationship between the state health authorities and the civil society was a ‘delicate collaboration’. Budgetary support increased initially and then tapered off, and release of funds remained erratic across the years. Despite these hurdles, the authors draw several lessons. First, to be effective, social accountability needs official endorsement from the top but at the same time it requires active facilitation at the community level by an autonomous agency. The pressure from both above and below creates countervailing power. Second, a strategic alliance can be forged between service users (citizens) and frontline health workers (duty bearers) that solves problems for both parties. The multi-level strategy adopted by SATHI allowed for these alliances at the local level, and provided a pathway for escalating the problems to a higher level.

The working paper is rich in detail with many vignettes and case-stories that bring the dynamics of patient-provider and community-health system interactions alive. Yet while it describes what could be considered a success story and a validation of social accountability for improving health service delivery, it also contains several notes of caution.

The most important question is whether state functionaries and authorities are genuinely interested in receiving feedback from the community, especially if it pertains to their own work, rather than the work of a subordinate. Without robust facilitation by an autonomous agency, community monitoring can remain tokenistic. Such an agency needs to be supported by the government, but also needs to remain at arm’s length in order not to be subverted. In the case of CBMP processes in Maharashtra, subversion has been happening since 2017 with funds being reduced and disbursements getting delayed, and continued support is uncertain. However, the authors conclude that the various community level and civil society networks that were strengthened in the earlier years remain robust, and that they enabled service delivery during the Covid pandemic.

The Future of Community Monitoring

This blog traces the dynamic journey of community monitoring of health services in India over the last twenty-five years. Community monitoring seeks to empower citizens to provide feedback to public authorities and experts. In essence, it challenges entrenched power relations between the expert-led health bureaucracies and citizens. The rural poor who are at the centre of concern are also at the bottom of hierarchical societies like in India. Certain enabling conditions in the global policy environment, a level of assurance among social activists, and an openness to review and change in the national government allowed community monitoring to slowly get institutionalized into everyday practice. Nonetheless, routinization has its pitfalls, as highlighted by the case study of Maharashtra.

The level of openness of the ‘state’ to citizen feedback can change over time and this can facilitate or constrain the process of community monitoring. While at the global level there is a continued emphasis on strengthening community processes and civil society engagement for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, the robustness of community monitoring cannot be assured without a strong civil society with adequate civic space in which to engage the state at different levels; and state mechanisms that are open to such persuasion. While the case study of Maharashtra provides some hopeful signs that the process can continue despite lack of state financial support, when civic space is severely constrained, such accountability-related conversations can be construed as anti-state action.