Picturing Accountability

Date: January 2021

Author(s): Naomi Hossain and Ismail Ferduos

Publication type: Blog

Published by: Transparency & Accountability Initiative (TAI)

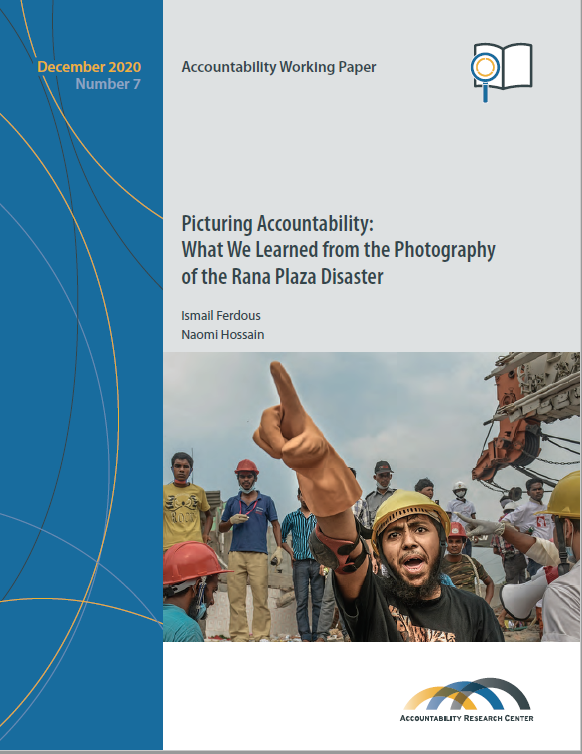

Note: This blog was originally published by Transparency & Accountability Initiative on January 13, 2021. What we learned from the photography of Rana Plaza  Figure 1 A worker leaves the site where the Rana Plaza garment factory building collapsed near Dhaka, Bangladesh. © Ismail Ferdous, 2013. Why we need pictures to tell complex stories Grand corruption, terrible disasters, and miscarriages of justice are complex failures of accountability. As practitioners and researchers working on transparency and accountability, usually with backgrounds in public policy, social science, or the law, we frame our messages about such complex failures with hard facts – about dodgy finances, broken laws, and false public statements. We find hard facts persuasive and definitive. Yet wordy arguments and statistical data rarely provide a clear or compelling frame for accountability. And campaigns without a clear and compelling story can neither garner popular support nor shift norms about acceptable public behavior. The hard fact now is that in a post-truth era, facts are no longer enough on their own. At some level, we already know this. So we always include a nice picture when we post a blog. No advocacy campaign is without photographs of (possible) beneficiaries. Cute gifs reinforce our Twitter threads. Yet, while we spend days honing our concepts and sentences, thinking carefully about audiences and verbal messages, we take a casual scattergun approach to our visual story-telling. What we learned from the photography of Rana Plaza Pictures of the Rana Plaza factory collapse that killed 1,134 workers in Bangladesh in 2013 made me rage and grieve. But they also taught me how powerful pictures could be for accountability struggles. Garment workers had been fighting for their rights for decades; workers at Rana Plaza were forced to work in an unsafe factory in large part because they lacked the unions that could have enforced their rights to safety. But in the horrific aftermath of the collapse, photographers built a powerful visual narrative about the need for answers and action that no decrying or measuring in words or numbers could hope to achieve. The pictures hit you frontally and deep inside your conscience. You asked yourself: is this the price of that disposable shirt from Gap or Top Shop?

Figure 1 A worker leaves the site where the Rana Plaza garment factory building collapsed near Dhaka, Bangladesh. © Ismail Ferdous, 2013. Why we need pictures to tell complex stories Grand corruption, terrible disasters, and miscarriages of justice are complex failures of accountability. As practitioners and researchers working on transparency and accountability, usually with backgrounds in public policy, social science, or the law, we frame our messages about such complex failures with hard facts – about dodgy finances, broken laws, and false public statements. We find hard facts persuasive and definitive. Yet wordy arguments and statistical data rarely provide a clear or compelling frame for accountability. And campaigns without a clear and compelling story can neither garner popular support nor shift norms about acceptable public behavior. The hard fact now is that in a post-truth era, facts are no longer enough on their own. At some level, we already know this. So we always include a nice picture when we post a blog. No advocacy campaign is without photographs of (possible) beneficiaries. Cute gifs reinforce our Twitter threads. Yet, while we spend days honing our concepts and sentences, thinking carefully about audiences and verbal messages, we take a casual scattergun approach to our visual story-telling. What we learned from the photography of Rana Plaza Pictures of the Rana Plaza factory collapse that killed 1,134 workers in Bangladesh in 2013 made me rage and grieve. But they also taught me how powerful pictures could be for accountability struggles. Garment workers had been fighting for their rights for decades; workers at Rana Plaza were forced to work in an unsafe factory in large part because they lacked the unions that could have enforced their rights to safety. But in the horrific aftermath of the collapse, photographers built a powerful visual narrative about the need for answers and action that no decrying or measuring in words or numbers could hope to achieve. The pictures hit you frontally and deep inside your conscience. You asked yourself: is this the price of that disposable shirt from Gap or Top Shop?  Figure 2 Relatives of missing workers in the Rana Plaza garment factory building that collapsed hold pictures of their family members in Savar, near Dhaka, Bangladesh. © Ismail Ferdous, 2013 Ismail Ferdous, an award-winning photojournalist who photographed the disaster and its aftermath in the victims and survivors’ lives, agreed to help me think through what photography means for accountability. From thinking together, we arrived at several conclusions (here for the full version of the paper).

Figure 2 Relatives of missing workers in the Rana Plaza garment factory building that collapsed hold pictures of their family members in Savar, near Dhaka, Bangladesh. © Ismail Ferdous, 2013 Ismail Ferdous, an award-winning photojournalist who photographed the disaster and its aftermath in the victims and survivors’ lives, agreed to help me think through what photography means for accountability. From thinking together, we arrived at several conclusions (here for the full version of the paper).

- Images are not optional or illustrative extras in accountability struggles

As we learned from the police murder of George Floyd in the US, iconic images are profoundly important for struggles for accountability in a digital era. Emotions and understandings of injustice are expressed visually and circulated in ways and on platforms unimagined a generation ago. The abstract concepts and wordy repertoires of the transparency, participation, and accountability field could learn from art and photography about using imagery to express complex ideas and build support – particularly among the more visually- and digitally-literate young.

- Photographing demands for accountability means testimony, not victimization

Images can mean emotional and moral responses that help widen and strengthen support for accountability, as Black Lives Matter showed. Yet international activism has long struggled with the racist politics and ethics of images of pain and suffering. These are uncomfortable matters. We concluded that visual evidence can be emotionally powerful and build solidarity across people and places without further victimizing its subjects. It matters not only what the images depict, but why and how they were produced, and by whom. Images that promote accountability through solidarity are not merely a bundle of digital commodities devoid of context; at their most powerful, they are a form of testimony rooted in fellowship and humanitarian principles.

- Images raise questions and demand answers about who is responsible

Images of the Rana Plaza disaster helped frame and amplify workers’ demands for accountability. These were more than powerful images of spectacular disaster or unimaginable human pain: they drew connections and raised questions about the industry as a whole, juxtaposing fast fashion fabrics and labels against broken bodies and smashed concrete. The question always asked rhetorically of disasters—how could this have happened?—took on a more forensic quality in many Rana Plaza pictures. The pictures made you ask —how is it that stitching household-name-brand clothing—the most innocuous and wholesome of products—could be so hazardous?

- Visual evidence only works with other accountability strategies in place

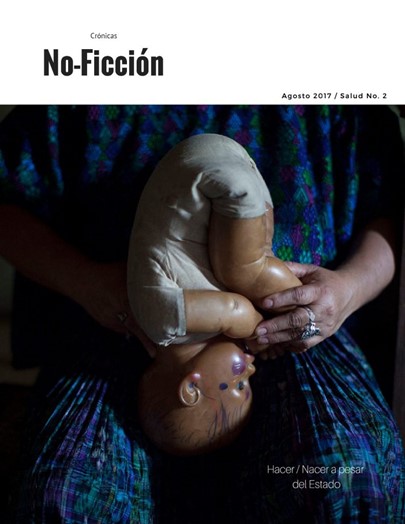

Despite their power, pictures of the effects of wrongdoing are not proof. The many images of brand labels in the rubble of Rana Plaza were unpleasant for the firms involved, but none lost business or reputation from the atrocious publicity. Pictures may be essential, but they rarely change the world on their own. So how can powerful visual evidence help activate pro-accountability measures? We think that visual evidence frames the demands for accountability: drawing connections and making plain the scale or severity of the human costs for failures, raising questions about the causes of and responsibilities for those failures, and about who pays the price.  Figure 3 Magazine cover showing a story about CEGSS health rights work in Guatemala. Photo Credit: Sandra Sebastián Harnessing creative collaborations for accountability Those of us working on transparency, participation, and accountability know that the arts matter, and we are getting better at creative collaborations. Some of the good examples I know of: the Accountability Lab (full disclosure – I’m on their Board) has had great success in engaging young people in accountability debates through their reality TV and singing competition formats. The Action for Empowerment & Accountability research program is uncovering the power of popular music and viral memes in popular debates about corruption and collective action. Here at the Accountability Research Center, we have supported the indigenous health rights defender organization CEGSS to recruit photojournalists to tell stories of their work to a wider audience (see Figure 3). In each of these examples, creative initiatives aim to mobilize wider support, set standards for public behavior, and frame questions about responsibility. This is an area the transparency, participation, and accountability can usefully invest in: building collaborative agendas with artists, musicians, and photographers that harness the power of creative expression for accountability. Rana Plaza taught us that pictures can help frame accountability demands clearly and memorably, turning problems into intolerable wrongs demanding action. But while we are using pictures and music in our work, we have yet to figure out when and how it works to advance accountability action. Thinking through the Rana Plaza experience, Ismail and I concluded that accountability action and research could do more to figure out what difference visual, artistic, and cultural repertoires make. We need more rigorous and direct research into what works, and why – as well as what to avoid, and how. Raising the emotional and moral stakes is risky, but worthwhile if it can raise awareness, build support, set new standards, or raise the social and material costs to those who seek to evade accountability. Financial accounting and legal liabilities will always offer formal entry points for accountability work, but the Rana Plaza photographs showed us that a more humane form of ‘accounting’ is crucial. The questions for the field are: what kinds of power is potentially unleashed by images and music? What are the risks of diving into creative collaborations? In picturing accountability more clearly, do we stand a better chance of making it happen?

Figure 3 Magazine cover showing a story about CEGSS health rights work in Guatemala. Photo Credit: Sandra Sebastián Harnessing creative collaborations for accountability Those of us working on transparency, participation, and accountability know that the arts matter, and we are getting better at creative collaborations. Some of the good examples I know of: the Accountability Lab (full disclosure – I’m on their Board) has had great success in engaging young people in accountability debates through their reality TV and singing competition formats. The Action for Empowerment & Accountability research program is uncovering the power of popular music and viral memes in popular debates about corruption and collective action. Here at the Accountability Research Center, we have supported the indigenous health rights defender organization CEGSS to recruit photojournalists to tell stories of their work to a wider audience (see Figure 3). In each of these examples, creative initiatives aim to mobilize wider support, set standards for public behavior, and frame questions about responsibility. This is an area the transparency, participation, and accountability can usefully invest in: building collaborative agendas with artists, musicians, and photographers that harness the power of creative expression for accountability. Rana Plaza taught us that pictures can help frame accountability demands clearly and memorably, turning problems into intolerable wrongs demanding action. But while we are using pictures and music in our work, we have yet to figure out when and how it works to advance accountability action. Thinking through the Rana Plaza experience, Ismail and I concluded that accountability action and research could do more to figure out what difference visual, artistic, and cultural repertoires make. We need more rigorous and direct research into what works, and why – as well as what to avoid, and how. Raising the emotional and moral stakes is risky, but worthwhile if it can raise awareness, build support, set new standards, or raise the social and material costs to those who seek to evade accountability. Financial accounting and legal liabilities will always offer formal entry points for accountability work, but the Rana Plaza photographs showed us that a more humane form of ‘accounting’ is crucial. The questions for the field are: what kinds of power is potentially unleashed by images and music? What are the risks of diving into creative collaborations? In picturing accountability more clearly, do we stand a better chance of making it happen?

Ismail Ferdous is an award-winning photojournalist based in New York City whose work covers social and humanitarian issues. While still living in Dhaka, Bangladesh, he began the project The Cost of Fashion, a photo and video advocacy project after documenting the Rana Plaza factory collapse, the worst industrial disaster in history. He then continued working on the same issue with the After Rana Plaza project. The project continues to spread awareness about the fashion industry and its negative effects on workers in Bangladesh. Ismail has presented at Tedx Maastricht and his article about photojournalism was published in Harvard Magazine. He is a regular contributor to National Geographic and has photographed for The New York Times Magazine, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Bloomberg News, MSNBC Photo, and Associated Press. Ismail’s work has been exhibited at Photoville, United Nation headquarters, numerous Dysturb exhibitions, The Rencontres d’Arles, Photolux Festival Luca, The Gallatin Galleries NYU, Tokyo Photograph Art Museum, 25CPW Gallery New York, the World Bank headquarters, and the Powerhouse Museum, among others. Ismail’s work can be viewed here: https://iferdous.com/. Naomi Hossain is a political sociologist, who is currently a Research Professor at the Accountability Research Center in the School of International Service at American University in Washington DC. She was previously employed by BRAC Research and Evaluation Division in Bangladesh, and the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex in the UK. Her research focuses on the politics of development, and she has written extensively about Bangladesh, disasters, protests, and women’s empowerment. She is the author of The Aid Lab: Understanding Bangladesh’s Unexpected Success (2017, Oxford University Press). Naomi’s work can be viewed here: https://nomhossain.com/.