Bottom-up Accountability in Uganda: Learning from People-centered, Multi-level Health Advocacy Campaigns

Date: February 2021

Author(s): Angela Bailey and Vincent Mujune, with a preface by Prima Kazoora

Publication type: Working Paper

Published by: Accountability Research Center

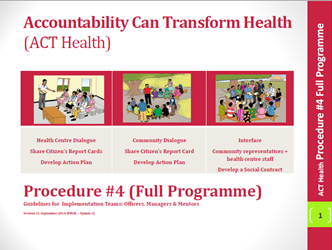

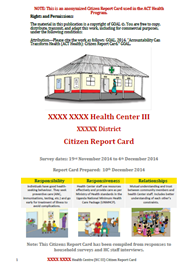

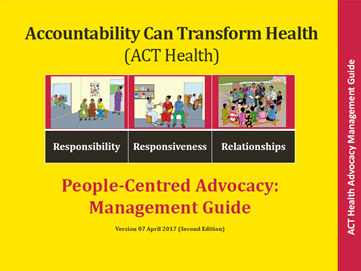

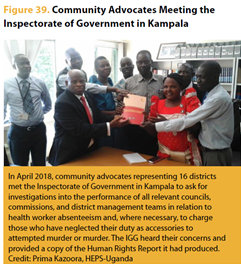

Uganda’s laws, policies and health sector strategies codify openings for citizen participation in planning and monitoring government services, yet these spaces are often inaccessible in practice. In response to this, a consortium of civil society organizations led by GOAL designed and implemented the Accountability Can Transform Health (ACT Health) program in Uganda from 2012 to 2018. This paper draws on program monitoring data, empirical evidence, and supplementary interviews to analyze how and the extent to which the ACT Health multi-level, people-centered advocacy campaigns strengthened accountability for health from the bottom up. The ACT Health program reviewed in this paper had two distinct phases. Phase 1, from 2014 to 2016, included a series of CSO-facilitated dialogues between community members and health workers in 282 government health facilities. These yielded action plans, which were then reviewed in follow-up meetings every six months. Phase 1 was designed to be evaluated through randomized control trial (RCT) research, which tested the impact of citizen report cards (information) and community-level dialogues on a series of 12 outcome indexes. Given the complexity of health system governance in Uganda, the ACT Health strategy anticipated that issues identified at the community-level would require coordinated citizen action to address bottlenecks above and beyond frontline health centers. After the RCT ended, Phase 2 of the program added a new approach: accompanying networks of volunteer grassroots community advocates from 98 health center catchments in 18 districts to organize, design, and deliver multi-level advocacy campaigns. In Phase 2, from 2016 to 2018, 396 community advocates identified advocacy priorities, then planned and delivered advocacy campaigns to a wide range of government officials up to the national level. In 14 districts, communities built advocacy campaigns around the complex issue of health worker absenteeism. The RCT intervention tested in ACT Health Phase 1 was based on the influential “Power to the People” research published in 2009, which reported that improved information through citizen report cards and facilitated dialogues between community members and health workers dramatically improved health outcomes (Björkman and Svensson 2009). While the “Power to the People” study remains influential in the transparency, participation and accountability field, researchers tested the intervention in 25 health facilities, resulting in a statistically under-powered RCT. Ten years later, the ACT Health RCT re-tested the intervention in 282 health facilities, increasing the statistical power of the analysis. The ACT Health RCT findings published in 2019 detected modest improvements in “treatment quality” and “patient satisfaction”, but found no evidence of improved health outcomes reported in the original “Power to the People” research a decade earlier (Raffler, Posner, and Parkerson 2019). The present paper reviews the ACT Health RCT findings, unpacking how key outcome measures such as “community monitoring” were operationalized and exploring the limits of the relatively “light touch” approach tested. Support to collective, multi-level advocacy campaigns in Phase 2 of the ACT Health program was part of the strategy from the beginning—it was neither tied to nor contingent upon the RCT findings from the Phase 1 intervention. Starting in 2016, community advocates (selected by other community members) collected data through direct monitoring of health facilities, analyzed that data, developed petitions, recruited allies, mobilized resources, organized collective actions, and directly engaged government officials from the village to the national level. CSO staff helped community advocates conduct their own political economy analysis, tapping into advocates’ knowledge of authorities and government systems. Independent monitoring of government services in Phase 2 was not a one-off exercise. Community advocates in 18 districts engaged in on-going monitoring to assess the effects of their advocacy campaigns. In almost half of the 98 health facility catchments, advocates leveraged their knowledge and skills to launch special advocacy campaigns to tackle additional challenges they had independently identified. In this multi-level strategy, prior experience with community-level dialogues (in Phase 1 under the RCT) helped community advocates to develop advocacy campaigns targeting sub-county and district officials. These subnational campaigns, in turn, fed into coordinated national level campaign actions on health worker absenteeism. Most strikingly, advocates from 14 districts combined their efforts to amplify citizen voice on the problem of health worker absenteeism, reaching national-level actors such as line ministries and parliamentarians. The impacts of these more strategic multi-level, people-centered advocacy campaigns were not studied by the RCT, which was designed instead to re-test the more limited, less intensive, and locally-bounded community-level intervention popularized in the earlier “Power to the People” study. The work in Phase 2 was more complex, as advocacy campaigns are dynamic and iterative processes whose elements cannot be rigidly programmed. This meant that the work in Phase 2 was not amenable to the experimental research methods used in RCTs, which are more appropriate for testing discrete and standardized interventions and short causal chains. This paper uses practitioner-led analysis of ACT Health program monitoring data to document outcomes and learning from these iterative advocacy processes in 18 districts. To capture the variation in government responsiveness, GOAL developed a “Heat Map” summarized here to show the scale and diversity of outcomes observed. Community advocates were tenacious and creative through 18 months of engagement with subnational (district) government officials. Figure S1 summarizes subnational government officials’ responsiveness to campaign asks as of June 2019 (one year after program funding ended). In five districts, government officials implemented commitments in response to citizen campaign asks. In three additional districts, officials went further and invited com-munity advocates to extend their independent monitoring to other sectors (such as education and construction). While 8 districts responded very well to community advocates, in 10 districts, subnational officials were either unresponsive or made commitments, but implementation was relatively limited. The data reveal nuance and variation in subnational government responsiveness to advocacy campaigns. This nuance—and related insights around change dynamics—would have been invisible in an approach focused on aggregated quantitative averages.  Key reflections from the ACT Health program (2014 – 2018) This working paper is a practitioner-led analysis of the full ACT Health program. The paper contextualizes key RCT findings, then explores outcomes and learning from the cycles of citizen-led engagements and government responses during Phase 2 advocacy campaigns. We anticipate that this study of people-centered advocacy will contribute to conversations about robust citizen-led engagements with the state, to incrementally deepen democracy in these universally challenging times. 1. The ACT Health RCT study provides limited insight into the ACT Health program approach. The RCT studied only the first, locally-bound phase of the ACT Health strategy, excluding the more strategic multi-level monitoring and citizen-led advocacy work after the RCT ended. RCT researchers concluded that “bottom-up accountability” was inherently weak (Raffler, Posner, and Parkerson 2019), even though the RCT indicators were too indirect to measure whether independent community monitoring was actually done. In contrast, Phase 2 saw active bottom-up monitoring by networks of community advocates who coordinated health advocacy campaigns in 18 districts. Studies (such as the present one) of more strategic, iterative, intensive, and multi-level accountability work provide richer insights into the dynamics of accountability relationships than the RCT study of a single discrete tactical component embedded in a broader strategy. 2. Externally funded programs can support citizens’ strategic efforts to directly engage the state and strengthen accountability. Rather than speaking for communities affected by poor service delivery, CSOs supported and accompanied citizen-led advocacy campaigns. Phase 2 of the program supported district networks of organized community advocates to: collaborate across multiple health facilities, deliberate and prioritize advocacy issues, orchestrate independent monitoring of multiple health facilities, analyze their findings, and direct evidence-based advocacy asks to government officials. ACT Health supported community-driven political economy analysis, expanding local advocates’ civic knowledge to develop context-specific strategies targeting powerful officials. In all 18 districts, community advocates directly engaged a range of government officials, meeting them in their offices, participating in budget planning meetings, going on the radio to ask officials to act, and many other creative tactics to capture attention of powerholders. As part of a joint campaign on absenteeism, advocates drew on material and analytical support from CSOs to overcome collective action barriers, navigate power dynamics, and directly engage national-level officials. Ensuring that advocacy agenda-setting power rests with citizens—the essence of the people-centered advocacy approach—proved possible even in a externally-funded project. 3. Independent, bottom-up monitoring and advocacy can trigger top-down system responses, changing accountability relationships. The multi-level advocacy campaigns in Phase 2 triggered top-down oversight, activating responses with potential for broader changes. CSO coaching and mentoring helped community advocates prioritize and target powerholders—and advocates then navigated politics, leveraging checks and balances among subnational authorities during their campaigns. In some cases, advocates reached nationally mandated bodies, triggering Inspectorate of Government offices’ independent investigation when district-level officials were insufficiently responsive to advocates asks. Government responses included: increasing monitoring and oversight of health facilities, reporting findings of their monitoring back to citizens, increasing resource allocations, acknowledging the role of advocates through official letters, and sanctioning on health workers. Government officials’ reporting their findings and corrective actions back to advocates indicate degrees of answerability and downward accountability from the state to citizens. Community advocates’ engagement with higher level officials led to greater recognition, which appears to have mitigated health workers’ reprisals (backlash) against citizens. Government officials at the sub-county and district levels in 8 (of 18) districts implemented commitments that met or exceeded community advocates “asks”. The range of responses by subnational government officials to community advocates’ campaigns reveal the potential for shifting power and accountability relationships between citizens and the state.

Key reflections from the ACT Health program (2014 – 2018) This working paper is a practitioner-led analysis of the full ACT Health program. The paper contextualizes key RCT findings, then explores outcomes and learning from the cycles of citizen-led engagements and government responses during Phase 2 advocacy campaigns. We anticipate that this study of people-centered advocacy will contribute to conversations about robust citizen-led engagements with the state, to incrementally deepen democracy in these universally challenging times. 1. The ACT Health RCT study provides limited insight into the ACT Health program approach. The RCT studied only the first, locally-bound phase of the ACT Health strategy, excluding the more strategic multi-level monitoring and citizen-led advocacy work after the RCT ended. RCT researchers concluded that “bottom-up accountability” was inherently weak (Raffler, Posner, and Parkerson 2019), even though the RCT indicators were too indirect to measure whether independent community monitoring was actually done. In contrast, Phase 2 saw active bottom-up monitoring by networks of community advocates who coordinated health advocacy campaigns in 18 districts. Studies (such as the present one) of more strategic, iterative, intensive, and multi-level accountability work provide richer insights into the dynamics of accountability relationships than the RCT study of a single discrete tactical component embedded in a broader strategy. 2. Externally funded programs can support citizens’ strategic efforts to directly engage the state and strengthen accountability. Rather than speaking for communities affected by poor service delivery, CSOs supported and accompanied citizen-led advocacy campaigns. Phase 2 of the program supported district networks of organized community advocates to: collaborate across multiple health facilities, deliberate and prioritize advocacy issues, orchestrate independent monitoring of multiple health facilities, analyze their findings, and direct evidence-based advocacy asks to government officials. ACT Health supported community-driven political economy analysis, expanding local advocates’ civic knowledge to develop context-specific strategies targeting powerful officials. In all 18 districts, community advocates directly engaged a range of government officials, meeting them in their offices, participating in budget planning meetings, going on the radio to ask officials to act, and many other creative tactics to capture attention of powerholders. As part of a joint campaign on absenteeism, advocates drew on material and analytical support from CSOs to overcome collective action barriers, navigate power dynamics, and directly engage national-level officials. Ensuring that advocacy agenda-setting power rests with citizens—the essence of the people-centered advocacy approach—proved possible even in a externally-funded project. 3. Independent, bottom-up monitoring and advocacy can trigger top-down system responses, changing accountability relationships. The multi-level advocacy campaigns in Phase 2 triggered top-down oversight, activating responses with potential for broader changes. CSO coaching and mentoring helped community advocates prioritize and target powerholders—and advocates then navigated politics, leveraging checks and balances among subnational authorities during their campaigns. In some cases, advocates reached nationally mandated bodies, triggering Inspectorate of Government offices’ independent investigation when district-level officials were insufficiently responsive to advocates asks. Government responses included: increasing monitoring and oversight of health facilities, reporting findings of their monitoring back to citizens, increasing resource allocations, acknowledging the role of advocates through official letters, and sanctioning on health workers. Government officials’ reporting their findings and corrective actions back to advocates indicate degrees of answerability and downward accountability from the state to citizens. Community advocates’ engagement with higher level officials led to greater recognition, which appears to have mitigated health workers’ reprisals (backlash) against citizens. Government officials at the sub-county and district levels in 8 (of 18) districts implemented commitments that met or exceeded community advocates “asks”. The range of responses by subnational government officials to community advocates’ campaigns reveal the potential for shifting power and accountability relationships between citizens and the state.

Angela Bailey Angela began working at the Accountability Research Center (ARC), an action-research incubator based at American University in Washington, DC, in August of 2016. Prior to joining ARC, Angela worked for international NGOs in various capacities in Liberia and Uganda. From April 2014 to June 2016, Angela worked with GOAL as program director of the Accountability Can Transform Health (ACT Health) program in Uganda. Angela holds a Master’s in International Affairs from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. abailey@american.edu | @participangela. I began working in Uganda in 2009 and during an eight-month consultancy in 2012, I helped GOAL to develop the ACT Health program approach. I compiled a literature review, conducted key informant interviews, and co-created the initial theory of change. When GOAL secured a larger grant to expand the ACT Health program, I was hired as the ACT Health program director and oversaw all aspects of planning, implementation, monitoring, and learning. I also worked closely with my co-author Vincent Mujune during the initial year of planning, preparing, and piloting of the people-centered advocacy approach before leaving Uganda in June 2016. In February 2018, I re-engaged with Ugandan colleagues and community advocates to better understand the processes and outcomes of the people-centered advocacy campaigns accompanied by the ACT Health program. While I have an intellectual stake in this analysis given my role in the pro-gram’s design and implementation, the time and physical distance enable me to critically examine and reflect on the effects of the people-centered advocacy work. Vincent Mujune Vincent led GOAL’s people-centered health advocacy work in Uganda from May 2016 to December 2020. He supported community-led processes using participatory evidence-generation and analysis methods to engage affected communities, build their capacities and strengthen the influence of marginalized households on the health system. Vincent is a member of Uganda’s Civil Society Budget Advocacy Group and has trained civil society actors on people-centered advocacy in Sri Lanka, Malawi, and Sierra Leone. vincentmujune@gmail.com | @vincentmujune. I started working with GOAL in 2014, initially supporting organizational development among GOAL’s many civil society partners. In 2015, based on my experience supporting direct advocacy by persons with lived experience of mental ill health, I began to develop materials and pilot the people-centered advocacy work in Bugiri District in 2015. In May 2016, I became Deputy Director of the ACT Health program. I was instrumental in supporting and guiding civil society organization (CSO) teams as they prepared community advocates to drive their own campaigns. This included refining training tools and processes, delivering workshops, and providing ongoing supervision and feedback to CSO staff in all districts. Positionality: Practitioners as Authors As co-authors of this paper, we acknowledge our roles as architects and stewards of the ACT Health program. Our closeness to the implementation brings strengths and weaknesses. As self-critical practitioners committed to learning and advancing participatory governance, our closeness to the ACT Health program enables us to bring to light multiple dimensions of a multi-level strategy and offer insights into the “black box of implementation.”