Unveiling Accountability in Uganda: A Linguistic Tapestry

In most Ugandan languages, there is no direct word or words that exactly defines or translates the term ‘accountability.’ As such, different words with varying meanings get used, even within the same language communities.

This blog is written by three native Ugandans, who work with the Africa Freedom of Information Centre (AFIC). AFIC is a pan-African, membership-based civil society network and resource center that promotes the right of access to information, transparency, and accountability across Africa. The authors explore some of the many ways the word ‘accountability’ is understood across Uganda, and reflect on the implications for their work

Meanings of accountability range from answerability and responsibility to the broader implications of transparency, integrity, and citizen engagement. AFIC sees public officials and civil servants as being entrusted with decision-making power and resources to perform public functions on behalf of and for the benefit of citizens, and for public good. They are thus expected to be responsible for their actions, and more importantly answerable for them. This calls for them to disclose public information so that citizens are in a position to appreciate how entrusted authority and resources are being exercised, and to facilitate the public to raise any questions and concerns if necessary.

Beyond information disclosure, AFIC concerns itself with empowering citizens to gain knowledge, skills, and tools necessary for them to hold duty bearers accountable and to provide feedback to relevant stakeholders for corrective measures. In this regard, therefore, accountability serves as a cornerstone for promoting good governance and fostering socio-economic development.

Uganda’s linguistic diversity

The “Pearl of Africa” is well known for its brilliant and breathtaking scenery but also its diverse cultures and languages.

It is home to 41 living indigenous languages and three living non-indigenous languages. The living languages fall into four main families – Nilo-Saharan (21), Niger-Congo (18), Creole (1), and Sign Language (1).

In Uganda, Luganda is the most widely spoken language in the central region. This is followed by English (also the official language since 1962), then Swahili.

Uganda has no national language, and many people speak in their local languages when engaging government services such as treatment in health facilities. Attempts to make Swahili a national language during the constitution-making process in 1993 were strongly resisted because it was associated by many with errant members of the armed forces who communicated in the language while terrorizing innocent civilians. Similarly, attempts to make Luganda a national language were resisted by people from other parts of the country, based on the mistrust people of different tribes have for each other.

Since 1962, English has been the only official language used in public offices, and official communications and meetings. The 1995 Constitution made English the official language but also allowed use of any other language “as a medium of instruction in schools or other educational institutions, or for legislative, administrative or judicial purposes”. An estimated 85% of the population speaks English with different levels of fluency. Pupils in lower primary are taught in their mother local languages; 15 are official languages of instruction. But from Grade Four onwards, English is the official language of instruction.

With the process of regional integration underway, the Cabinet in 2022 resolved to promote Swahili as Uganda’s second official language, to align with neighboring Kenya and Tanzania.

In this linguistic landscape, the concept of “accountability” weaves a complex narrative, reflecting the varied perspectives that enrich the nation. In exploring understandings of accountability across Uganda’s linguistic landscapes, distinct interpretations emerge, each contributing to the cultural nuances of accountability, which include its use and meaning.

Definitions of accountability

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines accountability as an obligation or willingness to accept responsibility or to account for one’s actions. It is key to note that what accountability means in different Ugandan languages, and who is being held to account for what, do not always align with these meanings in English – and that meanings also differ from community to community and language to language.

According to Prof. Gilbert Gumoshabe, a Senior Lecturer and Head of the Department of African Languages at Makerere University, Kampala, accountability is largely understood as a monetary or financial term, reflecting a political culture driven by monetary gain rather than service. He goes on to suggest that the reason that, “there’s no single word for accountability in Runyankole-Rukiga,” is because traditional Ankole society was not monetary; the same is true for many other local languages in Uganda rooted in non-monetary traditional cultures.

The imported English word “accountability” tends to be used only by people who have attained a certain level of education, and its meaning is evolving and malleable. This makes engaging with accountability initiatives difficult for people who do not speak or understand English, or have much formal education, especially rural women, youth, the elderly, and people with disabilities.

With no single word for “accountability” in Luganda or Runyankole-Rukiga, people often use the English word “accountability” in the middle of local-language sentences, without translation. When attempts at translation are made, a combination of words are used, but even these are likely to be interpreted in different ways, depending on the listener. During AFIC’s work building demand for accountability, the same staff member will use different words to explain accountability from one engagement to another. This can make the work challenging, especially among non-English speaking communities.

Ms. Stella Kanyesigye, a languages expert and Coordinator of Expanding Social Protection at Uganda’s Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development, observes that in Ugandan languages words have both a first and a second meaning. Using a combination of words often helps to bring closer the meaning of certain words, but makes exact translations difficult. She agrees with Prof. Gumoshabe that there is no exact word for accountability in Runyankole-Rukiga, and that the closest Runyakole-Rukiga word is embaririra (which she defines as “counting”). But she pairs it with enkozesa, which means “usage”.

Ms. Stella Kanyesigye, a languages expert and Coordinator of Expanding Social Protection at Uganda’s Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development, observes that in Ugandan languages words have both a first and a second meaning. Using a combination of words often helps to bring closer the meaning of certain words, but makes exact translations difficult. She agrees with Prof. Gumoshabe that there is no exact word for accountability in Runyankole-Rukiga, and that the closest Runyakole-Rukiga word is embaririra (which she defines as “counting”). But she pairs it with enkozesa, which means “usage”.

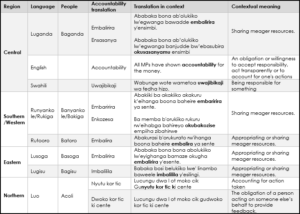

The following table looks beyond Runyakole-Rukiga and highlights some examples of the usage of the word accountability from the different regions in Uganda.

Contextual influences on the meaning of accountability

In most Ugandan communities, accountability is also context-specific. For example in politics, a politician or leader who positively influences policies and ensures accountable use of public resources may still not be considered accountable if he/she doesn’t also directly contribute to constituents’ personal needs, such as by attending and/or paying for burials, covering school fees, funding construction of religious institutions. That many leaders focus on amassing wealth for such activities (sometimes corruptly) in order to deliver on people’s expectations of ‘accountability’ is not seen as a contradiction.

Meanings of accountability are also influenced by regional, cultural, and gendered stereotypes. For example, it is quite often common to hear opinions that people from one region or another are corrupt thieves, or that one gender is more accountable and trustworthy than another. In other communities, there is street talk that people of a certain gender are bakuuzi (cheats) and do not contribute, but rather expect to be provided for.

AFIC has found that working to promote accountability in communities where chiefdoms and kingdoms formerly existed can be undermined by deeply entrenched cultural understandings. In a pre-colonial cultural context, kings and chiefs owned land and other assets, which they gifted to subjects as they pleased. As a result of this legacy, subjects were understood to have obligations towards their leaders. They demonstrated that they were accountable for fulfilling their obligations by, for example, providing payments to their chiefs and kings by giving a portion of their harvest and/ or directly pledging their labor to their chiefs and kings. People were held accountable by their leaders, and not vice versa; and people were not entitled to demand accountability for the usage of these resources. This historical, culturally-embedded inclination makes it hard to switch the script on who should be accountable to whom in AFIC’s accountability efforts. Even today, the idea of holding leaders accountable is seen as “indiscipline” given that traditionally accountability was upward from subject to ruler. AFIC has found that in communities where kingdoms didn’t exist, it is easier to inform and empower citizens to actively demand accountability from their civic and political leaders.

Lack of clarity about meanings has resulted in AFIC’s transparency and accountability campaigns being mainly carried out in English, and sometimes the four other main languages used by large proportions of the population. This excludes millions of people, which in turn affects the effectiveness of campaigns. Even in the four larger language groups, the lack of a common local word for accountability has limited the effectiveness of our campaigns. Adequate campaigns can be achieved through elaborate explanation and contextualization with examples, although this has additional financial and other resource implications.

The lack of a commonly understood and used meaning of accountability in different communities presents a major challenge for building effective demand for it. This is made even more difficult when local views of financial accountability see it as what they get from leaders to solve their personal problems, which is quite different from a public policy perspective on accountability.

Conclusion

This write-up has shared some examples of the multifaceted nature of the concept “accountability” in Uganda.

AFIC’s continued efforts seek to address associated challenges including the implications of multiple meanings of accountability for communication, the lack of appreciation of the key concept of public accountability resulting in poor targeting and messaging, ineffective campaigns, and lack of effective citizen participation, even when spaces for engagement may exist. Lack of adequate feedback from citizens in turn contributes to inefficiency and corruption in service delivery.

No one word defines accountability in Ugandan local languages nor is there a universal appreciation of what it means across different languages and tribes. There is still work to be done in strengthening the meaning and understanding of the word across Uganda’s regions and languages.