Repurposing Everyday Discourse on Social Accountability: A Precise, and Strategic Agenda from Dalit activists in India

Transparency, accountability, participation are contested concepts. Though these buzzwords are widely used, they tend to convey different meanings depending on the user. Dalit youth fighting caste oppression in the district of Bhilwara in the northwestern Indian state of Rajasthan articulated five principles (Swamy 2020), repurposing everyday discourse to communicate transparency, accountability and participation concepts in vernacular language: 1) jankari (information) knowledge about entitlements; 2) sunwai (hearing) the right to be heard with a written acknowledgement; 3) karyawahi (action) within a specified timeframe; 4) bhagidari (participation) at every stage of the policy process; and 5) suraksha (protection) for the complainant, who is at the risk of violent reprisal (Dey 2013). These principles are a powerful articulation of what accountability means to a category of citizens who experience endemic, systemic discrimination, and whose routine engagement with the state results in their disempowerment (Swamy 2019). Here we contextualize the first two principles.

The most common words used to describe information in Hindi are soochna or jankari. The first, soochna, is used officially to communicate, intimate, inform or notify the public of policy decisions or government actions. Used by the state to inform its citizens, what is conveyed or represented is factual information. The official use of soochna represents the power imbalance manifest in citizen-state relations in countries like India. These relations are embedded in languages—legal and bureaucratic—that signify the power of the state. Often official information is difficult to understand; it needs to be demystified or translated into idioms that citizens can understand. The language of the state also does not acknowledge other languages—those of socially excluded groups—as free and equal (Chandhoke 2005). Marginalized groups such as Dalits routinely experience violence by state and societal actors. Their efforts to seek recourse through institutions of rule of law—police or courts— typically results in their inability to register a complaint against the perpetrators of violence or worse, be wrongfully implicated as the wrongdoer. Thus, the repurposing of the official term soochna as jankari conveys the demand for relevant information that goes beyond simple facts and legalese, or pushing press releases for new policies or promotions, and represents a demand for relevant information about entitlements, how to access them, and platforms for redress.

The official use of soochna represents the power imbalance manifest in citizen-state relations in countries like India. These relations are embedded in languages—legal and bureaucratic—that signify the power of the state.

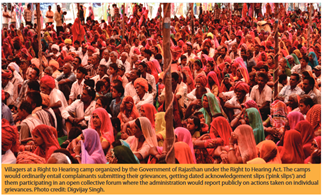

The second Bhilwara Principle of sunwai repurposes the everyday discourse on participation and accountability. In the day-to-day encounters with the Indian state, one rarely goes as a rights-bearing citizen. You go as supplicants, to pay a bribe, or with a powerful connection. Gram sabhas or village assemblies that, in principle, embody the ideal of universal participation in practice circumvent participation by excluding women, and lower caste groups. Even more exclusionary are caste panchayats, organized and run by upper caste men, these forums function as an agent of moral and social control. Emphasizing a right to be heard in inclusive forums that are free from coercion, the principle of sunwai, highlights the inadequacy of existing forums and mechanisms. This is especially true in cases where the actual abuses are harsh (such as caste and gender based violence), but also when the institutions of the rule of law (such as the police) that are supposed to act in ways that prevent violation of citizens’ rights are themselves under question. By adding this third important dimension of sunwai, grassroots activists broaden the ‘answerability’ and ‘sanctions’ aspects of accountability (Schedler 1999).

References

Dey, Nikhil. 2013. “India: The Long Road from Transparency to Accountability.” The Brics Post. Retrieved December 30, 2013 (http://thebricspost.com/india-the-long-road-from-transparency-to-accountability/#.WRYKmlPytE4).

Chandhoke, Neera. 2005. “Exploring the Mythology of the Public Sphere.” In Civil Society, Public Sphere and Citizenship: Dialogues and Perceptions, edited by Rajeev Bhargava and Helmit Reifeld, pp. 327-347. New Delhi: Sage Publication.

Schedler, Andreas. 1999. “Conceptualizing Accountability.” In in the Self-restraining State: Power and Accountability in New Democracies, edited by Andreas Schedler, Larry Diamond and Marc F. Plattner, pp 13-28 London: Lynne Rienner.

Swamy, Rakshita. 2019. “Bhilwara Principles: an Accountability Framework in Action.” Common Cause 38:2, 36-41.

Swamy, Rakshita. 2020. “From Peoples’ Struggles to Public Policy: The Institutionalization of the Bhilwara Framework of Social Accountability in India.” Accountability Research Center, Accountability Note 9.