Citizen Experiences and Challenges in Bringing Transparency and Accountability to Local Governments in Southern Mexico

Date: February 2019

Authors: Carlos García Jiménez

Publication type: Accountability Note

Published by: Unicam-Sur and Accountability Research Center

Versión en español: Experiencias y desafíos ciudadanos para instituir la transparencia y la rendición de cuentas en gobiernos locales del sur de México

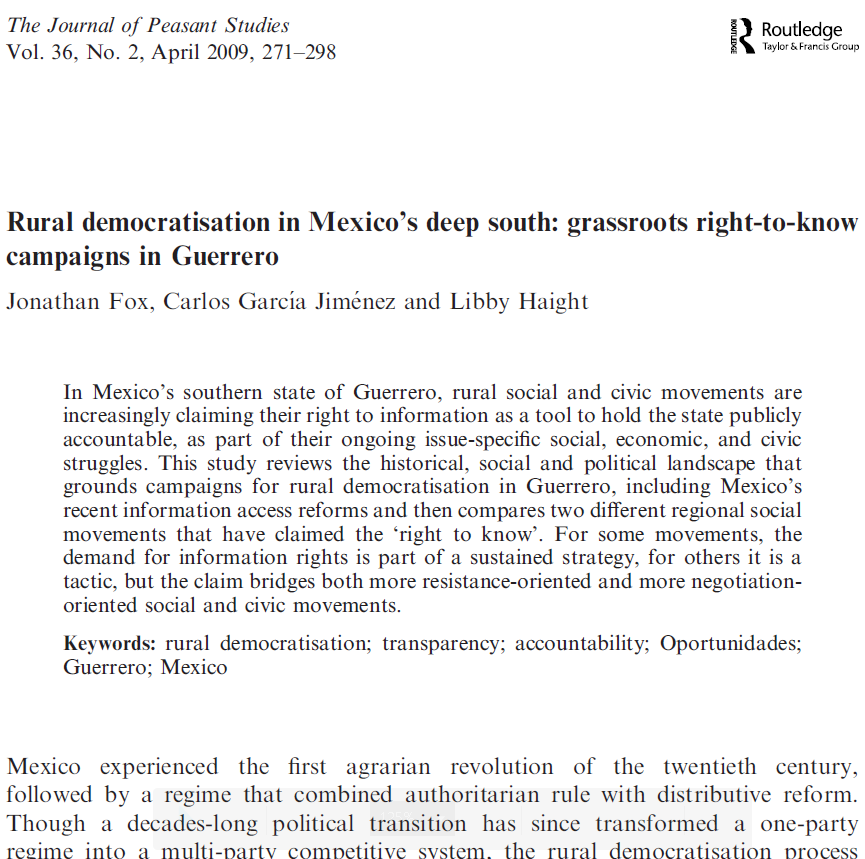

Despite Mexico’s constitutional provisions for transparency, accountability, and citizen oversight of government practice, in Guerrero—a southern state of Mexico which has historically fluctuated between periods of peace and violence—the entrenched elite continues to dominate. Nonetheless, grassroots citizens’ groups have been working against the current. With the accompaniment of the Universidad Campesina del Sur (The Peasants’ University of the South, or Unicam-Sur), a local organization that promotes alternative rural education and participatory research), they have been promoting and positioning these new concepts and practices of government. Citizen action for accountability continues, in spite of persistent practices of bad governance that include indifference towards citizen proposals and the use of the “fear factor” as a means of social intimidation. Modest citizen accomplishments—on issues of transparency in public works and the opening up of local municipal council meetings to citizen participation, for example—have opened cracks in the centralized and opaque structure of the entrenched elite. Over the last 15 years, these experiences of persistent voluntarism and self-taught citizen literacy, have led to the emergence of a pathway for citizen intervention in public affairs. We can describe the steps of this approach to citizen involvement as follows:

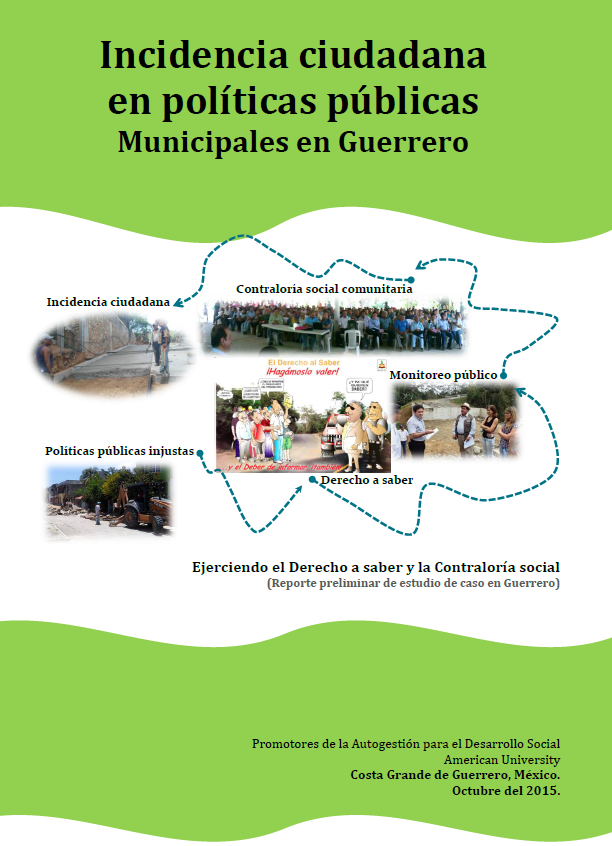

- Recognizing a problem and building empowerment to tackle it. Citizen groups become involved in problems that affect them and that are related to government action, and commit to changing their situations. The exchange of views about what is and what should be—drives citizens to investigate the causes and consider possible solutions.

- Exercising the right to know. Drawing on the public transparency laws and following the operating rules of government programs, citizens request and analyze official information, and then compare it to reality. In the process, they learn about the causes of the problems—and possible solutions.

- Monitoring and social oversight over public affairs. In light of the information obtained, the group then organizes to monitor the government action. With their evidence and arguments in hand, citizens approach government officials to correct their actions and address the problem. This type of citizen action sometimes leads to clear information about the project, course corrections, or project completion.

- Public policy advocacy. After evaluating the progress made, citizens conclude that to prevent the problem from recurring, flawed public policies or programs need to be changed, along with their decision-making and implementation processes. In order to engage the authorities in a dialogue among equals, communities must advance to a higher level of organization, knowledge, citizen education and training.

These citizen intervention processes have resulted in modest outcomes and the construction of a basic level of citizenship. Nonetheless, they have not carried over into permanent forms of citizen involvement because of the prevalence of adverse governmental conditions and the lack of essential resources for keeping these initiatives alive. These experiences are highly localized and focused on specific situations. However, they can inform similar citizen-led processes elsewhere and inspire citizens to build sustainable initiatives that promote transparency and accountability in local governments. The historic victory of the anti-establishment coalition (led by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador) in Mexico’s 2018 election, signals the start of a more favorable context for these citizen initiatives.

Carlos García Jiménez Carlos García Jiménez is an agronomist with a specialization in rural sociology from the Autonomous University of Chapingo (1986). He is originally from Ocotillo, Coyuca de Benítez, Guerrero, México. Currently he serves as Director General of Universidad Campesina del Sur (The Peasants’ University of the South, or Unicam-Sur); president of the board of Promotores de la Autogestión para el Desarrollo Social (Promoters of Self-Managed Social Development, or PADS); technical advisor to the Unión de Pueblos de Coyuca de Benítez y Acapulco (Union of Communities); advisor to the Permanent Forum of Social Organizations of Guerrero, founding promoter of the Plan de Ayala Peasant Movement of the 21st Century, Guerrero chapter. He is a member of the technical secretariat of the Pro-Municipal Coalition, a network of social organizations sponsored by Citizens/CIESAS.