Pananagutan: Accountability and the Struggle for Filipino Nationhood

In Filipino, the term accountability is often understood as pananagutan. Derived from the root word sagot or answer, pananagutan may be interpreted as the obligation to respond to questions regarding one’s conduct. The word, however, has a much broader meaning, unlike the term accountability which specifically refers to the process of holding actors responsible for their actions. Depending on the context or on how the word is used, pananagutan could mean not only accountability, but also obligation, liability, onus and responsibility.

It is also often understood in religious terms, since Pananagutan is the title of a popular church hymn in the Philippines. Composed by Filipino Jesuit priest Eduardo Hontiveros, the song proclaims that, “we are all accountable to one another” (tayong lahat ay may pananagutan sa isa’t-isa) since “God has gathered us all into His presence” (tayong lahat ay tinipon ng Diyos na kapiling Niya). The hymn eventually made its way into Philippine popular culture as it was featured in several films and television shows.

Because of its ubiquitousness, the song has greatly influenced how Filipinos understand accountability. But this common notion of pananagutan blurs the distinction between the answerability of those in power, and the responsibility of all citizens in promoting the common good.

However, there has been an ongoing attempt to create a culture of accountability, wherein those in power are made answerable to the people. This spirit of radical citizenship is reflected in Article II, Section I of the Philippine Constitution, which states that:

“Sovereignty resides in the people and all government authority emanates from them.”

Though unmistakably brief, this statement encapsulates the philosophical foundation of the Philippine nation-state: that rulership is lodged in every Filipino, and that the government is simply the instrument by which to realize their collective will.

This principle is further elaborated in Article XI entitled ‘Accountability of Public Officers’ (Kapanagutan ng mga Pinunong Bayan). Section of 1 of this Article declares that:

“Public office is a public trust. Public officers and employees must at all times be accountable to the people, serve them with utmost responsibility, integrity, loyalty, and efficiency, act with patriotism and justice, and lead modest lives.”

(Ang pagtitiwala ng bayan ay angkin ng katungkulang pambayan. Ang mga pinuno at mga kawaning pambayan ay kinakailangang mamalaging nananagutan sa mga taong-bayan, maglingkod sa kanila na taglay ang pinakamataas na pakundangan, dangal, katapatan, at kahusayan, manuparan na taglay ang pagkamakabayan at katarungan, at mamuhay nang buong kapakumbabaan.)

Because of these two provisions, it can be argued that the country’s system of governance is based on the principle of ‘borrowed authority,’ wherein power is viewed as the natural property of the people, which is then lent to selected leaders through the process of election. And since public officials are mere custodians of the power entrusted to them, they are then obliged to always place the common welfare ahead of their personal interest.

It is this principle of “borrowed authority” that the nation’s Founding Fathers had fought and died for. In his novel El Filibusterismo for instance, nationalist writer Jose Rizal (through his character Isagani), uttered the following lines:

“He who gives his gold and life to the State, has the right to require of it that he give him the light to better earn his gold and better conserve his life.”

This idea of Rizal was further developed by Emilio Jacinto, who was perhaps the youngest leader of Philippine Revolution. In his essay Light and Darkness, Jacinto emphasized that:

“The head of society is called the Government, and those who will exercise power are known as Public Officials. The purpose of Public Officials is the interest and welfare of the People. Whatever happens, it will be the Public Officials who will be held accountable.”

(Ang pinakaulong ito [ng lipunan] ay siyang tinatawag ng Pamahalaan o Gobyerno at ang gaganap ng kapangyarihan ay pinangangalananang mga Pinuno ng Bayan. Ang kadahilanan nga ng mga Pinuno ay ang Bayan, at ang kagalingan at kaginhawahan nito ay siyang tanging dapat tunguhin ng lahat nilang gawa at kautusan. Ano pa mang mangyayari, ang mga Pinuno ay siyang mananagot.)

Though the term pananagutan is absent in the text, Jacinto did use the word mananagot (will be held accountable), which clearly conveys the idea of accountability. It is this concept of pananagutan which has inspired citizens’ movements in the Philippines ever since.

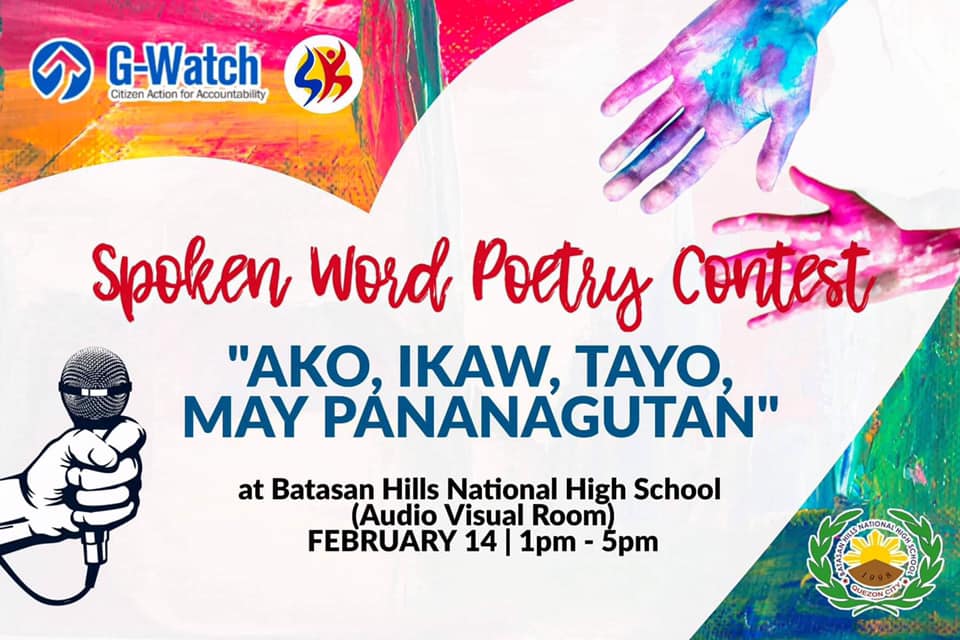

One such example is Government Watch (G-Watch), an independent national action research organization that works to promote dialogues in the Transparency-Participation-Accountability (TPA) field. On the second week of February 2020, G-Watch held an awareness-raising activity dubbed as “Ako, Ikaw, Tayo May Pananagutan” (AIM-P). The event was marked by simultaneous education forums in the cities of Naga, Pasig, Samal and Puerto Princesa.

An art exhibit was also set up on the campus of Mindanao State University (MSU) in Marawi; while in Quezon City, G-Watch youth volunteers organized a spoken word poetry competition involving senior high school students. Forums were also held the following day in Bacolod, Cebu City, Dumaguete, and in the town of Sibagat in the province of Agusan del Sur.

These diverse actions undertaken by the organizers shared a common objective: instilling the importance of accountability. By emphasizing the word pananagutan, G-Watch dismissed the view that accountability is a Western idea that is alien to Philippine society. It argued instead that the concept of pananagutan is closely intertwined to the nation’s history, and its people’s struggle for nationhood and freedom.