Open Parliaments for Inclusive and Participatory Oversight in Africa

Author’s Note – In Solidarity with Kenya’s Youth

This article was finalized just before Kenya’s June 2025 protests erupted in defense of dignity, justice, and a future free from fear. Young Kenyans filled the streets—risking everything simply to be heard, driven by hashtags, heartbreak, and digital defiance. I share this analysis in deep solidarity with all those demanding not just open parliaments, but parliaments that genuinely listen, protect, and serve their people. Openness must be more than a promise. It must meet people where they are: in their pain, their courage, and their call for meaningful change.

The concept of an open parliament centers on principles of transparency, access to information, and public participation. How these principles are interpreted and implemented, however, remains uneven. Despite the concept gaining momentum, evidenced by 55 OGP member countries having made a total of 162 open parliament commitments since 2011, many reforms remain narrow, such as livestreams or data portals that prioritize information dissemination over inclusive participation or institutional responsiveness. Parliaments and reformers rarely ask who these innovations serve, or how they shift power. Beyond transparency, meaningful openness demands co-creation—an intentional, collaborative process where citizens and legislators jointly design, implement, and refine parliamentary openness reforms.

1st Ordinary Session of the fifth Pan-African Parliament, Kigali, October 2018 (Paul Kagame, Creative Commons 2.0)

In many African countries, civic actors are calling for open parliaments to be reframed as more than a procedural checklist. Parliamentary monitoring organizations (PMOs), regional accountability networks, and civic tech platforms are advancing a deeper vision: parliaments as learning institutions capable of listening, adapting, and co-governing with citizens. This Accountability Keyword blog therefore highlights how these actors are redefining openness, not as a static end goal, but as an evolving process that centers equity, participation, and institutional responsiveness. In doing so, it positions open parliament as a learning framework, especially vital for legislatures seeking legitimacy among marginalized constituencies, with women representing the largest and most persistently excluded group.

Accountability Keyword in Context: Open Parliament

The term open parliament emerged alongside global movements for open government. A foundational moment came with the 2012 Declaration on Parliamentary Openness, which has since been endorsed by civil society parliamentary monitoring organizations. The declaration called for parliaments to be transparent, participatory, accountable, and technologically accessible. Yet even then, the concept leaned heavily on transparency: publishing votes, budgets, and transcripts, without fully grappling with issues of power, representation, or responsiveness. For example, while parliaments formally oversee national budgets, meaningful opportunities for public input particularly during budget approval and audit stages remain rare. According to the Open Budget Survey 2023, only 11% of the 117 countries assessed offered opportunities for public participation during the legislative review of audit reports, highlighting a significant gap in accountability mechanisms at this critical stage of budget oversight.

In Kenya, sustained advocacy by the International Budget Partnership (IBP) and its partners helped decentralize budget hearings that were previously held exclusively in Nairobi, enabling citizens to offer testimony from across the country. In one case, a citizen from Baringo County shared firsthand the lack of water access in their area, prompting a senior ministry official to respond. These kinds of grounded civic engagements show that transparency alone is insufficient without participatory processes that can influence institutional priorities and outcomes.

Over the past decade, a shift has been under way to move beyond transparency by centering public accountability, participation, and institutional responsiveness. Civic actors in the Global South, particularly in Africa and Latin America, have reinterpreted “open parliament” not only as a transparency norm but as a learning space, where citizen voice can challenge institutional inertia, and where parliaments themselves must adapt, reflect, and engage. This shift mirrors broader changes in how we understand accountability: from one-off demands (“yelp”) to continuous, responsive processes (“teeth”).

These continuous processes are not incidental; they result from the deliberate building of systems and structures designed to sustain accountability within the open parliament ecosystem, rather than serving as a “tick the box” exercise to gain public sympathy or recognition. In African contexts, this shift has been driven by legislative networks, watchdogs, and PMOs such as the Africa Parliamentary Monitoring Organizations Network (APMON), Civil Society Parliamentary Engagement Network (CSPEN), Mzalendo ‘Patriot’ Trust, Pan-African Parliament Civil Society Forum, Parliamentary Network Africa (PNAfrica), and Westminster Foundation for Democracy (WFD), among many others. Together, these actors have helped broaden public understanding of open parliament, shifting it from a technical agenda of data release to a more dynamic expectation of inclusion, dialogue, and responsiveness.

What’s the Problem? Parliaments as Opaque Institutions

Parliaments are designed to embody the principle of representation, yet budget decisions, committee work, and oversight functions are often conducted behind closed doors, with limited access to real-time data, voting records, or inclusive consultation mechanisms. Laws can be passed without scrutiny, oversight may become performative, and constituents, especially women, are left in the dark about decisions that affect their lives. Opacity often benefits political elites, maintaining traditional power structures. Thus, openness reforms frequently encounter institutional resistance, even when formally endorsed. Parliamentary openness is not simply about external pressure. Internal hierarchies such as powerful speakers, committee chairs, and senior party leaders, often control how transparent legislatures become. Gatekeeping by these actors can stall reforms and reinforce exclusivity.

That’s where Parliamentary Monitoring Organizations (PMOs) come in. These civil society actors monitor and evaluate the work of legislators to foster transparency, accountability, and public participation. Globally, over 190 PMOs track more than 80 national parliaments using tools like score cards, budget trackers, open data portals, and public participation forums. Yet even as the idea of “open parliament” gains traction globally, many legislatures remain structurally opaque and disconnected from the people they are meant to represent.

Nowhere is this disconnect more visible than in Kenya, where Parliament has become a central target of youth-led protest. The 2024-2025 demonstrations, catalyzed by opposition to the Finance Bill, evolved into a broader rejection of political elites. On June 25, 2025, protests erupted in at least 23 counties, led by youth with no central leadership—only hashtags, heartbreak, and digital defiance. Hashtags like #OccupyParliament signal growing disillusionment with elite-led politics and rising demands for grassroots representation. This reflects a deeper crisis of representative politics: many young Kenyans no longer view Parliament as a legitimate voice of the people, but as a symbol of exclusion and impunity.

This rupture in legitimacy is not just about a lack of transparency, it is about the failure of the Kenyan Parliament to engage, respond, and protect. The inability or unwillingness of legislatures, both in Kenya and elsewhere, to defend civic space, condemn police brutality, or acknowledge protest demands has further eroded public trust. These events underscore that open parliament reforms must go beyond information access; they must confront institutional silence, complicity, and the political alienation of an entire generation.

At the multilateral level, the Open Government Partnership (OGP) brings together governments and civil society to co-create national action plans, policy roadmaps to advance transparency and citizen engagement. These plans can include legislative commitments, but uptake has been weak. The OGP’s 2023–2024 annual report reveals that only 23% of member countries have embedded such commitments in their action plans. In Africa, these pledges are often modest and disconnected from broader civic strategies. For instance, Nigeria’s 2023–2025 OGP national action plan includes youth engagement and fiscal inclusion but omits any focus on parliamentary transparency or oversight.

Even where openness is formally endorsed, such as by signatories to the Declaration on Parliamentary Openness, implementation remains uneven and often incomplete. As the Declaration’s commentary notes, openness must be more than aspirational; it must be measurable, monitorable, and continuously improved. Without this, “open parliament” risks becoming an empty buzzword, detached from institutional practice and public impact. To avoid that fate, openness must be grounded in legitimacy. If young people, women, and other marginalized groups are withdrawing their consent from elite-led governance, then openness must be measured by whether parliaments are willing to evolve, to be observed, and to respond to the shifting demands of those they claim to represent. In this context, citizen-led monitoring becomes a critical bridge—linking transparency to genuine responsiveness. But for that bridge to be built, parliaments must first open themselves not just to scrutiny, but to transformation.

Who Gets Heard? Accountability Through a Gender Lens

Minister of International Relations and Cooperation, Maite Nkoana-Mashabane during the opening of the Fourth Pan African Parliament. (DIRCO, Creative Commons 2.0)

If accountability is about answering to citizens, we must ask: who gets to pose the questions? In many African legislatures, systemic barriers still limit the ability of women to meaningfully participate in – or benefit from – parliamentary processes. Applying a gender lens reveals a persistent asymmetry between who parliaments are accountable to, and whose concerns are structurally prioritized. Women legislators are often at the forefront of openness reforms, championing transparency and gender-sensitive oversight. Yet, their influence is frequently curtailed by rigid internal hierarchies and male-dominated party leadership structures. Strengthening women’s caucuses and enhancing their autonomy within party systems can therefore be a critical step toward genuinely inclusive openness reforms.

The Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) Benchmarks for Democratic Parliaments emphasize the importance of gender-sensitive legislatures. These principles are echoed in Open Government Partnership (OGP) national commitments from Kenya, Ghana, South Africa and others, which promote inclusive participation and transparent lawmaking. Yet in practice, mechanisms such as gender-responsive budgeting, inclusive public hearings, or women’s caucus-led oversight remain unevenly implemented and under-resourced across OGP Africa member countries.

Open parliament frameworks that ignore gendered exclusions can unintentionally reinforce them. For instance, increasing legislative transparency through digital portals is a step forward, but without mobile-first design, accessible formats, and translation into local languages, these reforms remain out of reach for many women, especially those in rural areas. This challenge is compounded by a persistent digital gender divide: in Sub-Saharan Africa, only 32% of women use mobile internet compared to 50% of men, and women are 13% less likely to own a smartphone. Despite over a decade of civic tech innovation, these structural inequalities such as limited digital literacy and unequal access to devices, continue to hamper equitable participation.

Without offline outreach, gender-sensitive legislative consultation, or simplified user interfaces, digital tools risk reinforcing exclusion rather than remedying it. Civic tech tools alone cannot substitute for structural legislative inclusion; they must be designed with the lived realities of women with limited connectivity in mind. The enduring gap between digital innovation and institutional responsiveness suggests that civic tech must evolve, not only to expand access, but to confront the political and social norms that continue to silence women’s voices. Models such as Kenya’s Senate Mashinani, where Senate sessions are held in counties to bring legislative processes closer to citizens, demonstrate how parliaments can proactively reach women and marginalized communities. Such “parliament-in-situ” approaches offer a concrete pathway for fostering inclusive participation, especially when paired with local civic engagement. This persistent reality invites us to broaden the meaning of “participation” beyond formal consultation or digital engagement.

Why Does ‘Open Parliament’ Matter?

Open Parliament matters because parliaments matter – but they remain among the least understood, least accessible, and least trusted public institutions. This has real consequences: when parliaments are opaque, unaccountable, or exclusionary, whole populations are cut off from meaningful representation and oversight. Reframing open parliament as a learning framework means viewing parliaments not as static institutions delivering one-way transparency, but as adaptive spaces that evolve through feedback, reflection, and citizen engagement. In this view, citizen-led monitoring and inclusive consultations are not optional add-ons, but they are core to how parliaments learn to govern more responsively.

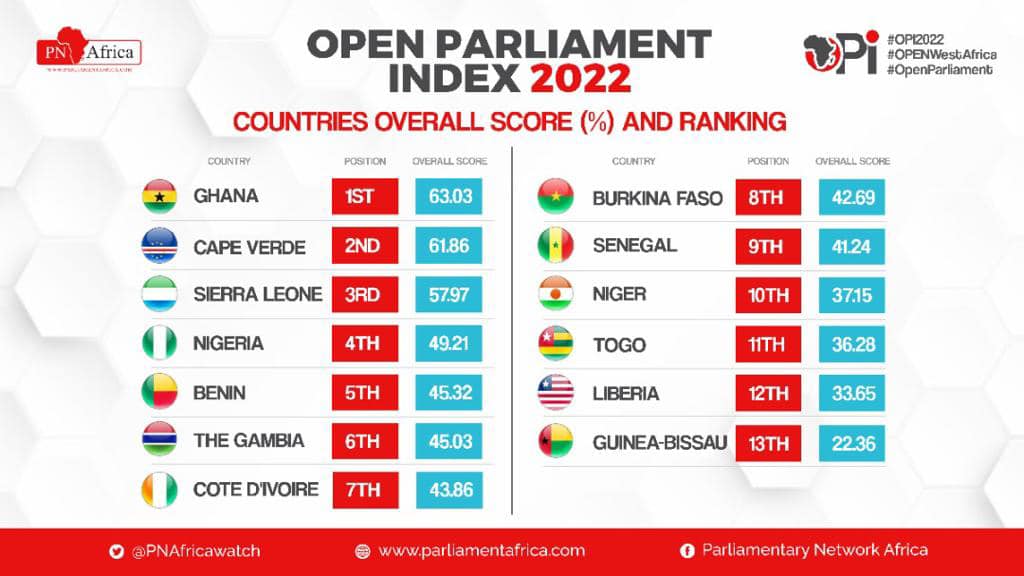

Platforms like the County Legislative Tracker (CLT), developed by WFD and Kenya’s Senate Liaison Office; Mzalendo Trust’s Dokeza (‘Share your Idea’), the Parliamentary Network Africa’s Open Parliament Index (OPI), and other regional tools are not just instruments of transparency, they generate critical evidence about what (and who) is being left out, offering parliaments concrete opportunities to adjust, correct, and grow. This shift reframes openness not as a checklist of outputs, but as an iterative process of institutional learning, one that strengthens already eroding citizen trust and builds legitimacy. Gender responsiveness, in this context, is a litmus test for inclusion. Are women shaping legislative agendas? Are women’s voices institutionalized in hearings and budgets? Are women-led civil society actors included year-round, not just symbolically? When parliaments learn to listen differently, they can govern differently and democratically. That is the promise of open parliament, not merely as a commitment to transparency, but as a learning framework grounded in accountability, where inclusion is measured by whether women’s voices shape legislative outcomes.

Yet the stakes go beyond institutional reform. In moments of political repression, the silence, or complicity, of parliamentary leaders and legislators can further erode public trust. During Kenya’s June 2025 crackdown, civil society groups and media outlets reported internet disruptions, alleged abductions, and the use of force against protestors. Amid these serious violations, few members of Parliament spoke out publicly, and leadership remained largely silent. In such moments, the absence of an institutional response, from parliamentary leadership, oversight committees, or even vocal caucuses within the legislature, can be perceived as tacit approval. This deepens public disillusionment and complicates trust between citizens and the very institutions meant to represent and protect them.

Closing Reflections: Open Parliament as a Practice, Not a Promise

Open parliament must be more than a governance buzzword. It’s a recalibration of how power, participation, and oversight interact. Yet across much of Africa, and despite being central to democracy, many parliaments remain among the least accessible institutions. Civic actors are pushing for change in a growing movement to make parliaments not only more transparent, but also more accountable and responsive. Still, the path to meaningful openness carries real risks.

The May 2025 arrest of IT developer and digital activist Rose Njeri underscores how precarious this work can be. Njeri built a civic tech tool designed to facilitate informed citizen engagement with parliament by allowing users to send emails directly to key parliamentary officials, ranging from the Clerk of the National Assembly to members of the Finance Committee, registering objections to the 2025 Finance Bill with a single click. Authorities charged her under Kenya’s cybercrime laws, claiming the tool “interfered with the normal functioning of the systems.” Her detention, which ended when the case against her was dismissed as defective, sparked widespread public outrage and highlighted a deeper issue: openness requires political protections for those who enable public participation.

Without such safeguards, “open parliament” risks becoming symbolic rather than substantive. Importantly, Kenya’s youth and women are not just calling for inclusion, they are demanding a redefinition of power. Protesters chant “Not Azimio, not UDA, just the people,” rejecting elite-led political processes altogether. This signals a deeper disillusionment with representative politics. Open parliament must therefore go beyond procedural access to become politically responsive. The disconnect between parliament and the street cannot be ignored.

While the 2012 Declaration on Parliamentary Openness laid essential groundwork, rapid technological advancements over the past decade necessitate revisiting these principles. Updating global standards could provide renewed commitment and clear benchmarks tailored to today’s digital governance landscape. Kenya’s experience also shows that openness is not just a reform agenda, it is a tool of protest. Rose Njeri’s civic tech tool wasn’t simply about transparency; it became a platform for direct digital dissent. In this context, openness can be radical. It can confront institutions, not just collaborate with them. Protesters are using open parliament tools to demand change, not through symbolic consultation, but through direct, grassroots action.

As we approach the International Day of Parliamentarism and the 2025 OGP Global Summit in Spain, the message is clear: declarations are not enough. Parliamentary openness must be ambitious, lived, and continuously refined, so that parliaments truly represent, listen, and respond to all. A genuinely open parliament is not built in a single reform cycle; it must be practiced, challenged, and continuously learned into being. Because if parliaments cannot learn to listen and respond, they risk losing the very legitimacy on which democratic governance depends. The true test of openness is not whether information is shared, but whether marginalized voices, especially women’s, can shape decisions and hold power to account. As the Kenya case shows, openness is not neutral; it can be instrumental in either deepening democracy or exposing its limits. As global actors gather to renew their commitments at the OGP Global 2025 Summit, now is the time to redefine openness not as performance, but as practice.