Auditing by the People: The Collective Conceptualization of Public and Social Audits in India

Whether in the field of public administration or corporate accountability, the term audit (from the Latin ‘to hear’) is often associated with technocratic forms of oversight—an exercise best left to “experts.” But what happens when this technocratic term is repurposed by grassroots public accountability campaigns striving to (re)establish the democratic spirit of public monitoring?

Reflecting on over three decades of direct involvement with struggles for public accountability in India, the three authors share how bottom-up accountability campaigns have shaped the reframing of this technocratic term, both democratizing and institutionalizing information-based participatory monitoring initiatives in India.

Repurposing ‘audits’ in accountability struggles

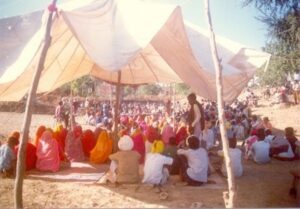

In the early 1990s, a grassroots campaign to enforce minimum wages in rural public works programs began repurposing the term ‘audit’ by organizing village-based ‘public audits’ of development expenditure in their area. In open, deliberative forums, called jan sunwai by their organizers, villagers and workers in the state of Rajasthan urged governments and policy makers to listen to, and act on their testimonies of on-the-ground realities. They used the right to information (RTI) to compare their testimonies with official records, seeking to overturn the loss of their livelihoods and wages.

A jan sunwai at KotKirana, Rajasthan, 1994. (Social Work Research Centre, Tilonia, Rajasthan)

The grassroots campaign for the RTI, initiated by the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) in central Rajasthan, developed into one of India’s most robust contemporary social movements. In synergy with the jan sunwai it incorporated ‘public audits’—information-based participatory democratic initiatives— into its campaigns for public accountability.

In Rajasthan, the first round of public audits of the 1990s resulted in local (panchayat) policy changes, providing access to information and asserting the people’s right to audit government expenditure. A decade later, India had a national Right to Information law, and the first legislation making statutory audits (officially called ‘social audits’) mandatory in the National Rural Employment Guarantee Law (2005). Access to information and the systematic use of it for seeking democratic accountability grew together.

Over three decades, rights-based campaigns in India have used public audits as one of many strategies to publicly scrutinize government policy and implementation. In this sense, public audits are essentially shaped and designed by social movements and campaigns, free of statutory requirements and state obligations. However, experience shows that without some government support, public audits and their findings are often ignored by officials. And bottom-up public audits are difficult for resource-poor, grassroots campaigns to organize at large scale.

A jan sunwai in Jharkhand, 2007 (Suchi Pande)

Consequently, from 2005, rights-based campaigners began to consistently use lessons drawn from public audits to influence statutory social audits, seeing them as a participatory democratic practice in the formal institutions of policy making and implementation. The political opening to institutionalize audits offered by the rights-based national employment guarantee legislation expanded; similar social audits have since been extended to thirteen social sector programs of the government.

Social movements and grassroots campaigners are therefore currently invested in expanding the scope of official social audits by actively engaging a range of state and national government agencies, including autonomous national oversight agencies such as the Supreme Court, and the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG)’s national office. They see the nurturing of a bottom-up democratic spirit of public audits in large-scale state-led processes as inseparable from their long-term goal of advancing citizen-centric approaches to government oversight and accountability.

In this iterative evolving process, public audits continue to offer new guiding principles for official social audits, as does the growing engagement and experience of autonomous oversight agencies.

Co-construction of auditing standards: mutually reinforcing public and social audits

Since their origins in the NREG law and subsequent spread to other sectors, social audits have been unevenly implemented across India. In 2011, the CAG’s office assessed the national state of social audits, emphasizing the uneven implementation, and provided a new opportunity to strengthen social audit implementation.

Learning from ongoing struggles to enforce social audits, and recognizing the vast experience of applying audit principles, over a decade, public accountability campaigners and progressive audit officials have collaborated to developing simple, foundational principles for institutional design. These included the separation of implementing and auditing agencies to avoid direct conflict of interest; ensuring financial and functional autonomy of sub-national social audit agencies to insulate them from political interference; ensuring the participation and protection of ordinary people in social audit processes; and dedicating budget allocation for social audits in social welfare schemes and programs. This cross-fertilization of experience has enriched the practice of auditing as a mode of government oversight.

But, in equally important ways, learning also came from grassroots campaigns. The Bhilwara Principles, articulated by Dalit youth in Rajasthan in their struggles against caste oppression, were incorporated into the national standards for social audits. They stress the importance of institutional responsiveness in auditing, and recognize that it requires compliance institutions to have the capacity to act on the findings of social audits.

With renewed interest and credibility afforded by the engagement with the CAG’s office and the Indian Supreme Court, social audits have gradually been incorporated into other sectoral programs: disability welfare, juvenile justice, education, and welfare entitlements of building and construction workers, among others.

It is important to recognize that the grassroots innovation of the jan sunwai has given birth to two powerful and parallel processes of citizen-centric accountability: public and social audits. While qualitatively different, the public and social audits are mutually reinforcing. The public audits keep pressure on official commitments for citizen oversight including through social audits, and auditing principles in turn shape and sharpen the ongoing effort by social movements to build robust and innovative processes of public oversight and monitoring.

Social auditors verify government information prior to social audit, Telangana. Credit: SSAAT-Telangana

With strategic support from allies in the national CAG office, public accountability campaigners are collaborating on updating national social audit standards to ensure the state does not back track from its official commitment on participatory information initiatives. A new national task force has been consulting civil society and local and mid-level auditors across different states in 2024, to further fine tune and update the national auditing standards developed during the first round of collaboration in 2016-17. A key focus in this round is on building autonomous social audit agencies, specifying procedures for follow- up on social audit findings, and activating grievance redress processes.

In the further development of social audits, several public accountability campaigners now engage and dialogue with political heads of state, high level ministry officials and civil servants, and provide technical advice to state governments on organizing social audits. They also partner on curriculum development and lead social audit facilitator trainings. These activists, then, have been recognized as experts, and been positioned inside official spaces, to influence the design and practice of social audits.

For some, this may be viewed as a form of bureaucratization of a grassroots innovation. While concerns about this institutionalization of grassroots information-based monitoring initiatives by the state are valid, public accountability campaigners in India have striven to imbue social audit processes with direct citizen participation, while continuing to retain the democratic sanctity of public audit processes.The public audit processes exclusively designed by social movements and rights-based campaigns, have remained independent and innovative. They do not merely watch over statutory social audit processes, they also continue to make public audits an important part of the lexicon and practice of citizen-centric social accountability.