A Novel Attempt to Break the Language Barrier in Research

What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.

– William Shakespeare, Romeo & Juliet

Language is known to be the medium of knowledge creation and dissemination of ideas. However, it is important to analyse who is the creator of that knowledge, who is consuming it, what is the purpose of that knowledge and most importantly is the language of that knowledge acting as a barrier or a gateway in the process of social change. This leads to answer an important question- how can the language of research become the language of the people? What are some of the challenges in delivering language of research to the language of people, especially when knowledge is produced in a language different from that of the people?

This piece will explore the above mentioned question through Accountability Initiative’s (AI) attempt to take Social Accountability theory, produced in English to change-makers and development professionals in the Indian grassroots, through its vernacular course, called Hum Aur Humaari Sarkaar (HHS).

HHS is a learning programme in Hindi (one of India’s widely spoken vernacular languages), to empower grassroots leaders to undertake a critical analysis of how government functions and delivers key public services. The aim is to build community leaders by equipping them with evidence-based research and tools to engage effectively with government, monitor social welfare programmes, and design appropriate interventions to demand accountability and improve public service delivery. The course is delivered by AI’s Field Associates who are uncomfortable speaking in English, supported by the national team, well-versed in English.

One of the key modules taught in the course is on Social Accountability. Social Accountability mechanisms as well as tools are neither new nor foreign to India. India has seen the rise of many accountability tools in action, from the Right to Information to the ASER[1] survey to mention some. However, availability of social science literature, both social science theory and applied social research, in vernacular languages is scarce. The research that has been encouraged in India is in English and dominated by American and European models and frameworks (Sarma and Agrawal 2010)[2].

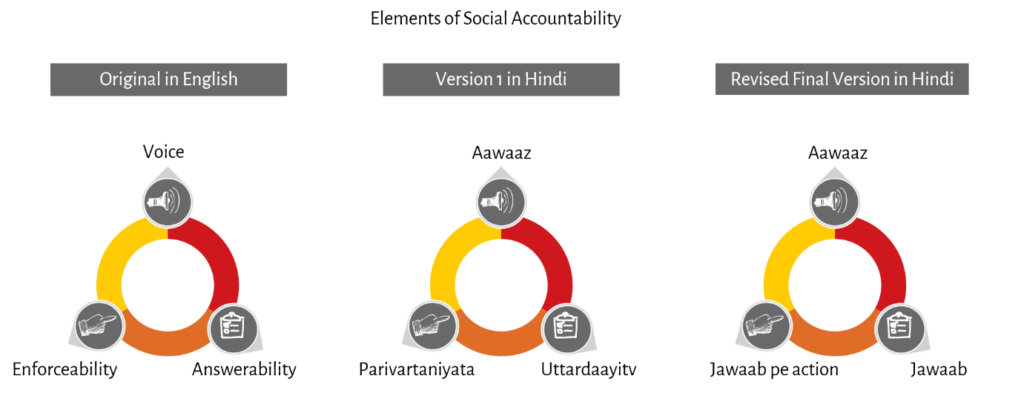

One of the theories taught in the course also lends from a European model explaining the three elements of Social Accountability as voice, answerability and enforceability (Camarago and Jacobs, 2013)[3]. Voice here is understood as a means through which people express their preferences and opinions and demand accountability from power holders. Answerability is defined as the obligation of the power holder to provide an account and the right to get a response. Answerability is understood to be triggered by Voice. Finally, Enforceability refers to a situation where, when the answers received are not satisfactory, consequences are expected to exist and be executed.

During the first round of content development for HHS, the national team put together the theory on Social Accountability that would enable grassroots change-makers anchor their experiences of claim making. The first hurdle faced was that of conceptual translation. The ideas proposed in highly theoretical papers by Camargo and Jacob (2013)3; Fox (2015)[4]; Newell and Wheeler (2006)[5], Gaventa and Mcgee (2011)[6]; and Aiyar (2009)1 needed to be explained to our Field Associates first, then discuss with them the relevance of the content for our purpose and finally collectively take the decision on what would be taught and how it would be taught. The many attempts to translate the papers failed- as no translator was able to capture the essence of the research. Words such as ‘social accountability’, ‘tools of social accountability’, ‘tactical and strategic approaches’ to promoting citizen voice, and other such words and phrases could not be encapsulated in Hindi without changing the meaning. The communication of ideas was entirely dependent on discussion and explanation sessions that the national team conducted for the Field team.

The research that has been encouraged in India is in English and dominated by American and European models and frameworks.

‘Elements of social accountability’, made it to the final curriculum. The team felt this concept was crucial to explain social accountability, as participants would be able to associate with this construction of the concept most, and once understood would be able to expand on it through their own experiences.

The second hurdle came in the linguistic translation of the ‘elements of social accountability’. Voice became ‘aawaz’, with great difficulty answerability became ‘uttardaayitv’ and with further more difficulty enforceability became ‘parivartaniyata’. The technically accurate translated words for answerability and enforceability were not only strenuous to pronounce, let alone remember, but also far away from colloquial language spoken and understood by our participants. Direct linguistic translation from English to Hindi just did not work.

This led to another round of deliberations. The team began decoding the essence of each word and what it meant. Voice was simplified to mean an aggregation of people’s voices and ‘awaaz’ was retained. Answerability was understood as the government’s ability/obligation to reply or give an account or share information with those voices. The suitable word in Hindi that would capture the meaning of ‘answerability’ accurately was ‘jawaabdehi’. However, this was the word also used describe ‘accountability’- causing confusion between ‘accountability’ and ‘answerability’. Finally, the word chosen to depict ‘answerability’ was kept simple- ‘jawaab’, literally meaning ‘answer’. Enforceability, was understood as the right to have action taken or enforced on the unsatisfactory answers received from the government, however the current translation ‘parivartaniyata’ literally meant the condition, intent or skills to enforce change or action- a word with difficult enunciation and use, not directly linked to ‘jawaab’, and missing the meaning to a certain extent. The simplest way of conveying the meaning of enforceability was ‘an action taken on the answer or jawaab received’, which gave birth to ‘jawaab pe action’- literally translated as ‘action on answer’. The three words began to link with one another- this was important.

These new words stuck with the audience. Our Field Associates claimed that the response to this section improved considerably. Participants started reflecting on their own work, sharing stories of voice, answerability and enforceability and the recall value of the three words in post-course evaluation also increased.

Apart from simplifying the language, we have also found the use of sharing examples extremely useful to convey theoretical concepts to grassroots audiences.

What worked for us in practice, as Fox (2017)[7] proposes in his theory was that we used words that our participants could relate with, the theory taught was grounded within their cultures, allowing the participants an opportunity to add further value to the concepts through their own lived experiences.

While the process has been challenging, we found the language of research can be delivered in the language of the people- especially since many ideas are trans-ideological, with language being the only barrier to taking this knowledge to the public.

This content was originally published on February 2, 2020 by Accountability Initiative. Read the original post here.

References

[1] Posani, B. and Aiyar, Y., 2009. State of Accountability: Evolution, Practice and Emerging Questions in. In AI Working Paper (p. 2).

[2] Sarma, S.K. and Agrawal, I., 2010. Social science research in vernacular languages. Economic and Political Weekly, pp.36-40.

[3] Baez Camargo, C. and Jacobs, E., 2013. Social accountability and its conceptual challenges: An analytical framework.

[4] Fox, J.A., 2015. Social accountability: what does the evidence really say?. World Development, 72, pp.346-361.

[5] Newell, P. and Wheeler, J. eds., 2006. Rights, resources and the politics of accountability (Vol. 3). Zed Books.

[6] McGee, R. and Gaventa, J., 2011. Shifting power? Assessing the impact of transparency and accountability initiatives. IDS Working Papers, 2011(383), pp.1-39.

[7] Fox, J., 2017. History and Language: Keywords for Health and Accountability. IDS Opinion.